I am the son of a soldier, and indeed the son of a Desert Rat!! Our father served as a Royal Engineer during WW2 in North Africa & Italy as part of the famous 8thArmy under the equally famous General Bernard Montgomery. Dad’s little brother Terry served as a 2nd Lt in the London Irish Rifles and lost his life in action in Italy during WW2. Our Great Uncle Charlie Pook, RE, D.C.M. was an “Old Contemptible”, a phrase used to describe the outnumbered British troops at the start of WW1. This phrase came from an order of the day from the Kaiser which mentioned, “Sir John French’s contemptible little Army” But this little army held off the larger German army until reinforcements arrived and counterattacked. Charlie’s Brother William saw action as a soldier during WW1, and then went on to become a member of “Dads Army” during WW2! Charlie and William’s father, my Gt Grandfather RSM John Pook also served as a soldier for over 20 years, his father-in-law my Gt Gt Grandfather Hon Lt Quartermaster Charles Sanderson was also a soldier who served in India & the UK for many years. Another branch of our family tree, my Grandfather Edgar Butler’s family, the Butlers, seemed to have a knack for dying in battle, 2 Gt Uncle’s, and 3 cousins (All Butlers) lost their lives in action during WW1, and there were probably other Butler relations who also lost their lives during WW1 that we are not aware of yet. Fortunately, at least 6 other Butlers who served in the armed forces managed to survive WW1.

Last but by no means least the Ahern’s have served in the Boer War, and I believe in the War for Independence in Ireland, and during recent times in the Irish Army and the British Army. There are many more relations from all branches of our family tree who have served and continue to serve in the armed forces; they all have stories to tell. Maybe too many to mention here! But hopefully, many of their stories will appear here. Over the years I looked deeper and deeper into their individual histories, the deeper I looked I began to realise that I had slowly but surely turned a passing interest into an obstinate hideous fascination. It was probably when I discovered the full-service history of one of my distant Butler cousins who joined the Buffs militia in 1907 and attended training every year, rose through the ranks to sergeant, fought on the western front, and died in the battle of the Somme in 1916. His every movement, promotion, award, misdemeanour, and pension was listed along with all of his personal details including his parents, siblings, wife and children. All of this personal detail brings home the true horror of war and the terrifying consequences it can bring down on innocent families.

Most of our ancestors/ relatives in the armed forces have left us something, most of it indirectly, some left a few words in a family Bible, a photograph, etc. From these few scraps of information I have attempted to weave their lost lives into the stories and histories of their lives and make it interesting, I hope I have done them justice. Some of them made the ultimate sacrifice and gave their lives for their countries. I and many others feel that their sacrifice should be immortalised and memorised for posterity.

I have had to decipher a huge amount of information to piece together our ancestor’s lives. I hope you enjoy reading it as much as I enjoyed re-creating and discovering their lives in the armed services.

These stories do not appear in any particular order.

Walter Butler 1898 – 1916 (Our 4th Cousin) Boy Soldier

Throughout history children have been involved in many military campaigns, the classic drummer boy, bugler, messenger boy, and munitions carrier, the list goes on and on. Boys have for centuries taken part in the actual front line fighting, using weapons of war, and still, continue to do so to this day.

Many of us as children played at being soldiers or with toy soldiers and probably thought nothing of it. Little did we realise in our innocent childhood that other children all over the world were not playing, but partaking in real wars. It should come as no surprise that even our own family has had a boy soldier in its ranks.

Walter Butler our distant cousin was one of about 250,000 boys and young men under the age of 19 who managed to join up to fight in WW1. The age of 19 was the legal limit for armed service overseas. Many more were turned away for various reasons.

On Tuesday the 4th August 1914, Britain declared War on Germany, two days later on Thursday 6th August 1914; Walter Butler was in the town of Chatham and joined the Royal West Kent Regiment.

Why did our 4th cousin join up only two days after England had declared war on Germany? Why did he join the Army in the nearby town of Chatham?

To attempt to answer these questions we need to go back to Walter’s early life.

He was born on 31st July 1898 in Sittingbourne, his father Thomas Henry Butler who was born in 1861, died at the beginning of August 1898 and was buried on the 10th August 1898 when he was 36 years of age. Walter never knew his father, and Thomas probably never even saw his son.

Things must have been tough for Olive, Walter’s mother; she lost her husband Thomas a few days after Walter was born, and she already had four children to care for, Helen, Mary Ann and Charlotte, her daughters aged 15, 13, and10, and her son Leonard aged 3, they all needed their mother to look after and provide for them.

It seems that Olive’s life was, to say the least complicated. According to the 1911 census record, it stated that she had had, 11 children, 9 of them still living. Presumably from 2 partners. Walter had a number of half-siblings including an older brother Edward who also served in the British Army.

Three years later in 1901 Olive was probably finding it hard to make ends meet. She and three of her children were now living at 10 Arthur Street, Milton Regis, Sittingbourne; her occupation is stated as Charwoman. Olive was now living with her oldest daughter Helen Nicholls and her husband and their young family; their 2- year-old daughter Florence. H.

Ten years later in 1911 Olive’s circumstances seemed to have improved, she was now living at 30 Mill Street, Milton Regis with her eldest son Leonard aged 16 years who was now a Brickfield labourer, and Walter aged 13 was at school. There is no mention of Walter and Leonard’s other two sisters, they were probably married. Walter, or rather his families luck was about to take a turn for the worse. Olive, Walter’s mother died at the age of 50 in 1912. Walter and his siblings were now essentially orphans.

Walter’s brother Leonard was 17 and working as a brickfield labourer and probably just about able to support himself.

Walter’s father died when he was ten days old and then he lost his mother when he was just 14; Walter probably matured quickly and had to go out to work to support himself. He had one older brother and three older sisters; maybe he went to live with one of his older siblings once his mother had died. Or he may have returned to his sister, Helen Nicholls in Arthur Street Milton where he and his family previously lived soon after his father died in 1898. According to his Military record, he was residing in Chatham in 1914.

Britain declared war on Germany on the 4th August 1914, two days later on the 6th August 1914 Walter Butler was in Chatham; he joined The Royal West Kent Regiment. According to his Attestation Paper, he was 18 years and 6 days old, the minimum age of joining up was 18 years, and it appeared that Walter was just old enough, very convenient for Walter.

Walter Butler lied about his real age when he joined up. In actual fact, Walter was only 16 years and 6 days old when he joined up. He probably looked older than his 16 years. He needed to be a minimum of 5 feet 3 inches tall and physically fit. It would appear that Walter met the official criteria for joining the army. Did he enlist in Chatham because it was far enough away from his home town, or did it just suit him here in Chatham?

As the Attestation form was filled out and completed, Walter had to sign his name after the following statement. The recruit above named was cautioned by me that if he made any false answer to any of the above questions he would be liable to be punished as provided in the Army Act. The questions were then read out and the recruit was made sure that he understood the answers he had made before taking the Oath.

That was it Walter had taken the Oath and made a false statement like many others before and after him.

Men and boys from every walk of life and all over the country felt the need to join up. Most did it for King & Country, others out of duty, and for some, they saw it as a great adventure, and maybe an escape from their life of poverty and hard labour. Maybe for Walter Butler, it was for all of these reasons that he joined up.

He had made a conscious decision to join the army and also to lie about his age. Walter did not wait for the famous Kitchener poster to appear before he joined up. Kitchener’s first appeal for men to join up was published on 11th August 1914, Kitchener’s poster, “Wants You” appeared for the first time in September 1914. By then Walter had been a soldier for nearly a month. Was he caught up in war fever, did he see a chance for an adventure, we shall never know.

His life so far had not been particularly easy, losing his father when he was 10 days old and then his mother when he was 14. Soon after losing his mother he started work as a Mill Labourer, in Sittingbourne Paper Mill.

At least Walter did not join up using an assumed name as many did. If that had been the case it would have made it more difficult for me to track him down. Some men and boys did join up using a false name for a variety of reasons; this made tracking them down very difficult for their relations, then and now.

Recruitment officers were paid two shillings and sixpence (about £6 in today’s money) for each new recruit, and would often turn a blind eye to any doubts they had

about age. At the same time, some officers thought that fresh air and three square meals a day in the army would do some of the more under-nourished boys a bit of good.

One in 5 under-age soldiers was sent home and discharged within a month of joining up. They were sent home either because they admitted that they were under age or they were too small to fight on the front line.

During 1916 the War Office agreed that if parents were able to prove that their sons were underage, they could be sent back home. Both of Walters’s parents were now dead, and we have no knowledge of what his siblings thought of his actions. In early 1916 Walter was, according to War Office records 19 years and 8 months of age, whereas, in reality, he was 17 years and 8 months old.

I can only presume that Walter may have told a couple more untruths on the day he signed his joining up papers. I say this rather than lies, as we really do not know the exact circumstances of his life, and I think we should give his statements the benefit of the doubt. I am sure that Walter was aware, and he had read the section on the Attestation form that states, “You are hereby warned that if after enlistment it is found that you have given a wilfully false answer to any of the following seven questions, you will be liable to a punishment of two years imprisonment with hard labour.”

Prior to this statement on his Attestation form, the question is stated, “ Have you resided out of your Father’s house for three years continuously in the same place or occupied a house or land of the yearly value of £10 for one year, and paid rates for the same, and in either case, if so state where……..” Walter’s answer was No.

I firmly believe that most people could actually answer Yes or No to this question and be truthful. Walter’s answer could have been Yes followed by No; maybe Enlistment officers gave guidance on answering this ambiguous question.

Looking at other Attestation forms some state Yes and No to this answer depending on circumstances.

The next question was.

“Did you receive a Notice, and do you understand its meaning, and who gave it to you?” The answer given was a Yes and the person who gave the notice was Sgt E. Skiggs, of The Buffs.

I think this may be a question given and answered by a soldier on the day of enlistment to the man enlisting.

I think the authorities, on the whole, turned a blind eye to most of the minor discrepancies, untruths, lies and false information, call them what you will, that were entered on many of the official forms. Any serious or larger discrepancies of information were usually rejected immediately.

Walter had to undergo basic training first, probably in a camp in Kent or Sussex. As he was one of the first recruits to join up after the outbreak of war he may have been lucky enough to receive a full complement of kit, uniform and rifle. Later recruits would not be so lucky and would have to make do with their own clothes and a wooden replica rifle.

The new recruits would have to learn Military discipline, how to march and also how to use a rifle and bayonet against the enemy. An enemy that they had yet to meet. For most of these men and boys, the transfer to Army life was a harsh wake-up call to the reality of being a soldier in 1914. But now they had all taken the oath for King and Country, the next stage for most of these men and boys would be overseas service in France and Belgium to join the fight against Germany.

The regiment that Walter Butler had joined was the 8th (Service) Battalion of The Royal West Kent Regiment; it was formed at Maidstone, the County town of Kent, and was part of Kitcheners 3rd new army (K3) during September 1914. Soon after this, the battalion moved to Shoreham to join the 72nd Brigade, 24th Division and then moved to Worthing in Sussex until April 1915.

The battalion then moved back to Shoreham in April and then later in 1915 moved to Blackdown. If nothing else Walter had seen life and a fair part of the South East of England.

The 8th Battalion, The Royal West Kent Regiment mobilised for war on Monday 30th August 1915. Walter Butler who was now just 17 had spent nearly a year training to be a soldier. Private Walter Butler, No L10423 was now going to war, his battalion crossed the channel and landed in Boulogne, probably the first time he had ever left England.

According to Walter’s medal card, he and his battalion were in France on 30th September 1915. Once the Battalion had landed in France their training continued as they moved across France towards the area of their first battle, Loos. The battle of Loos which began on 25th September 1915 and continued through the Autumn until 15th October 1915 was a large British offensive involving 6 divisions. It was the first time that the British used poison gas. This offensive attack by the British was however once again used in supporting a larger French attack, the Third Battle of Artois.

The 21st and 24th Divisions had only very recently arrived in France and had not yet seen the front line trenches. These infantry units began moving from St. Omer on 20 September 1915, with marches of over 20 miles throughout successive nights.

The British reserves including Walter Butler in the 8th Battalion, The Royal West Kent Regiment, including other British regiments were held in reserve during the beginning of the battle. These reserves were at first held too far from the main battlefront to be immediately useful and were unable to efficiently exploit the early battle successes. After this and succeeding days they were bogged down and into attritional warfare for very limited gains.

In late September during Saturday 25th and Sunday, the 26th September 1915, the 21st and 24th Division were in action around the area of Chalk Pit Wood and around Bois Hugo, Chalet Wood and Hill 70 Redoubt. This was to be their baptism of fire and probably the first time that Private L10423 Walter Butler aged 17 had seen action.

Walter the boy soldier during these few days in September 1915 would have been exposed to artillery fire, rifle and machine gun fire, maybe grenade attacks and possibly witnessed a horrendous new type of warfare, poison gas. It is a wonder that he survived this momentous battle, but survive it he did.

By the 27th September 1915, the 21st and 24th Divisions had sustained severe casualties and were withdrawn from the front. The 8th Royal West Kent’s lost approximately 580 men out of a possible full strength of their battalion of 750 soldiers. Walter must have witnessed and seen fellow soldiers fall to enemy action; he may even have had to help wounded soldiers in their hour of need.

Walter had a cousin, coincidentally named Walter who also saw action at the Battle of Loos. His full name was Walter Edward Butler, a sergeant in another Kent regiment, the 6th Battalion the Buffs. Maybe the Butler cousins tramped past each other when moving up or down to the trenches in the front line on the Western Front.

Both Butler cousins survived this battle, whereas 59,000 of their fellow soldiers from many regiments did not, they lost their lives at the battle of Loos.

During the last few months of 1915, Walters’s battalion of Royal West Kent’s required much-needed manpower to replace the high casualty rate that they suffered during the battle of Loos. While they were waiting for troop replacements the battalion would have been stationed behind the front lines resting and recuperating from their recent battle losses. But with the new replacement troops bolstering the battalion they would be constantly training and preparing for whenever orders came in for the regiment to relieve other regiments in the front line.

Christmas 1915 for Walter Butler was more than likely spent in France, probably for him it was his first Christmas away from home and family.

Early in 1916 the Royal West Kent’s were just about up to strength and would have spent some time in the front line relieving other regiments. They, in turn, would be

relieved so that they could rest, recuperate and re-equip before once again seeing action in the trenches.

At some stage between late 1915 and early 1916 Walter and his battalion were transferred from the area around Loos in France to Belgium and the infamous Ypres salient.

The 8th Battalion of the Royal West Kent Kent’s diary for March 1916 puts the battalion in Sanctuary Wood trenches and Belge dugouts, they sustained several casualties including 2nd Lieutenant Gascoyne who was wounded and suffered gas poisoning. While the battalion was in this area they also provided working parties in the Ypres Salient, probably repairing roads, track-ways and communication trenches. They were transported to the Salient by train and worked primarily in an area called Asylum.

Towards the end of the month, they moved to the Dranoutre area in Belgium, where on the 28th March 1916 Private Walter Butler, who was only 17 years and 9 months old, was wounded and subsequently died of these wounds on the same day.

One unverified account states that he was on duty as a sentry in the trenches when a gunshot wound fractured his skull.

Private Walter Butler was buried in the Commonwealth War Graves cemetery at Dranoutre Belgium. The Imperial War Graves Commission (the forerunner of the CWGC) states on its documentation concerning the information that was to be inscribed on individual’s gravestones, states NONE for the age for Walter. This was not uncommon, but maybe somebody knew he was not yet 18.

The entry in Sittingbourne’s local paper, The East Kent Gazette is as follows

East Kent Gazette – Saturday May 27 1916

Death

Butler – On March 28th, 1916, in France, Walter Butler, Royal West Kent’s, the beloved youngest son of the late Olive and Thomas Butler, aged 19 years.

When this death notice was published in the local paper and at the time of his death Walter was the “beloved youngest son”, aged just 17 years and 9 months.

I have discovered that in 1918 the following text was published in Sittingbourne’s local paper, from his sisters and brothers.

East Kent Gazette – Saturday March 30 1918

IN MEMORIAM

Butler – In ever loving memory of our dear brother, Walter Butler, who died, somewhere in France, March 28th 1916.

“To live in the hearts we leave behind is not to die” From his loving Sisters and Brothers.

According to the official war diary of the Royal West Kent Regiment and the Commonwealth War Graves Commission records, Walter Butler was killed and buried in Belgium. However the newspaper records from the same time, states that Walter Butler died somewhere in France. Maybe the information regarding Walters fate in 1917 became somewhat blurred for various reasons. There is a phrase somewhere that may make some sense of this – “The fog of War.” Having said all that, Dranoutre in Belgium where Walter was last in action and was then buried is very close to the French/Belgian border, in fact Dranoutre is approximately 2km from the French Border.

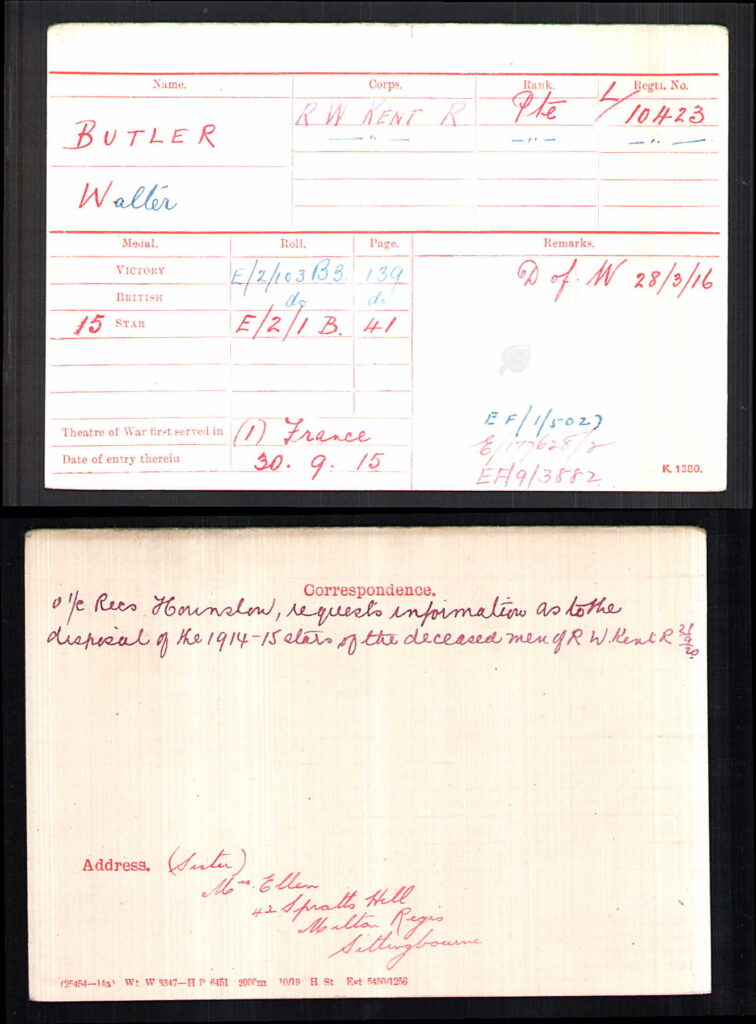

On the reverse side of Walter Butlers Medal Index Card is the following handwritten statement and address –

“O i/c Recs Hounslow, requests information as to the disposal of the 1914-15 Stars of the deceased men of the R W Kent R 21

9

20

Address. (Sister)

Mrs Ellen

42 Spratts Hill

Milton Regis

Sittingbourne

It was unusual for personal information such as address and or next of kin to appear on Medal Index Cards. This rarity is fortunate for us as we are able to complete another link in Walter’s short life and continued history.

Presumably, Walter’s sister Helen, had contacted the Military Records office and requested his medals and maybe his Memorial Plaque and scroll as well.

Walter was awarded the following Medals for his war service, 1914/ 1915 Star medal, The British war medal 1914-1920, and The Victory Medal 1914-1918. This group of three medals were given the affectionate names of Pip, Squeak and Wilfred.

However, and according to the EKG his half brother Edward who was also a serving soldier during WW1 received his brother’s medals.

When these medals were issued during the 1920’s it coincided with a popular comic strip published by the Daily Mirror newspaper. This comic strip had three animal characters Pip the dog, Squeak a penguin and Wilfred a young rabbit. The storey goes that A. B. Payne’s batman during the war had been nicknamed “Pip-squeak” and this is where the idea for the names of the dog and penguin came from. A.B.Payne was the cartoonist. The three names of the animal characters were associated with the three campaign medals being issued to the many thousands of returning servicemen, and the nickname stuck.

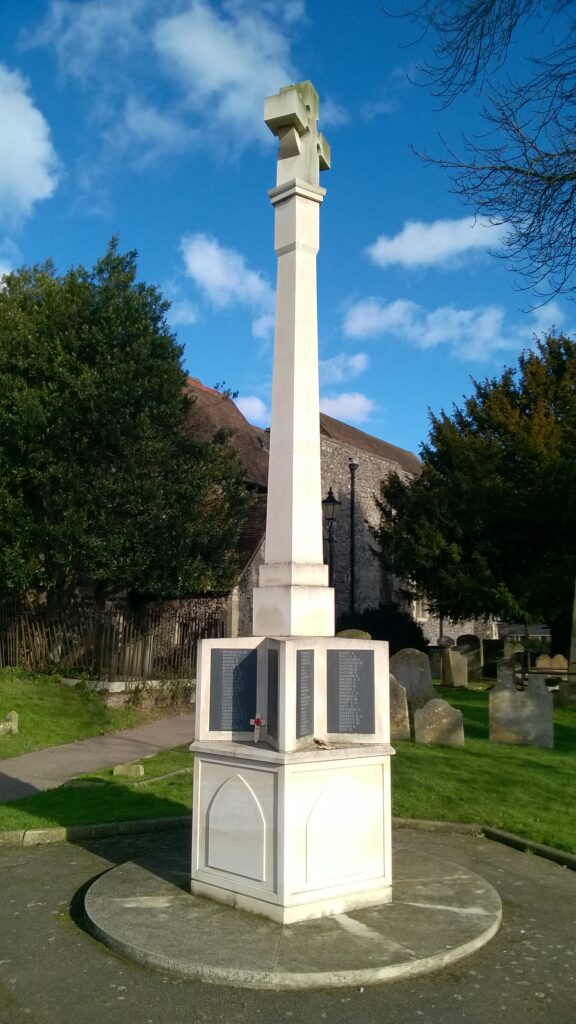

The Milton War Memorial situated in Milton Churchyard.

Walter Butlers Medal Index Card (On file at the National Archives) below.

Walter’s siblings may have been sent a photograph of his original grave, by the then Imperial War Graves Commission (now the Commonwealth War Graves Commission). The original grave would have been marked with a simple wooden cross. By 1917 the Commission had managed to send out about 12,000 photos to next of kin to try and alleviate the grief of losing a loved one. Eventually, these wooden crosses would be replaced with the permanent headstones that we all now recognise.

A War gratuity of £9-00 was paid to his sister and Legatee Helen E Nicholls in 1919, also paid in 1919 was a separated amount of £ 6-13-6.

The Royal West Kent Regiment has its own Cenotaph; it stands in Brenchley Gardens in Maidstone and is dedicated to the regiment’s dead of WW1. It was designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens, who was responsible for the Cenotaph in London.

Walter was the first and youngest of our Butler relations to die during World War 1 but, he was not to be the last ………………

Two pictures taken by Felicity Barry of Walter Butlers Headstone and the CWGC Cemetery where he is buried at Dranoutre, Belgium, Autumn 2017.

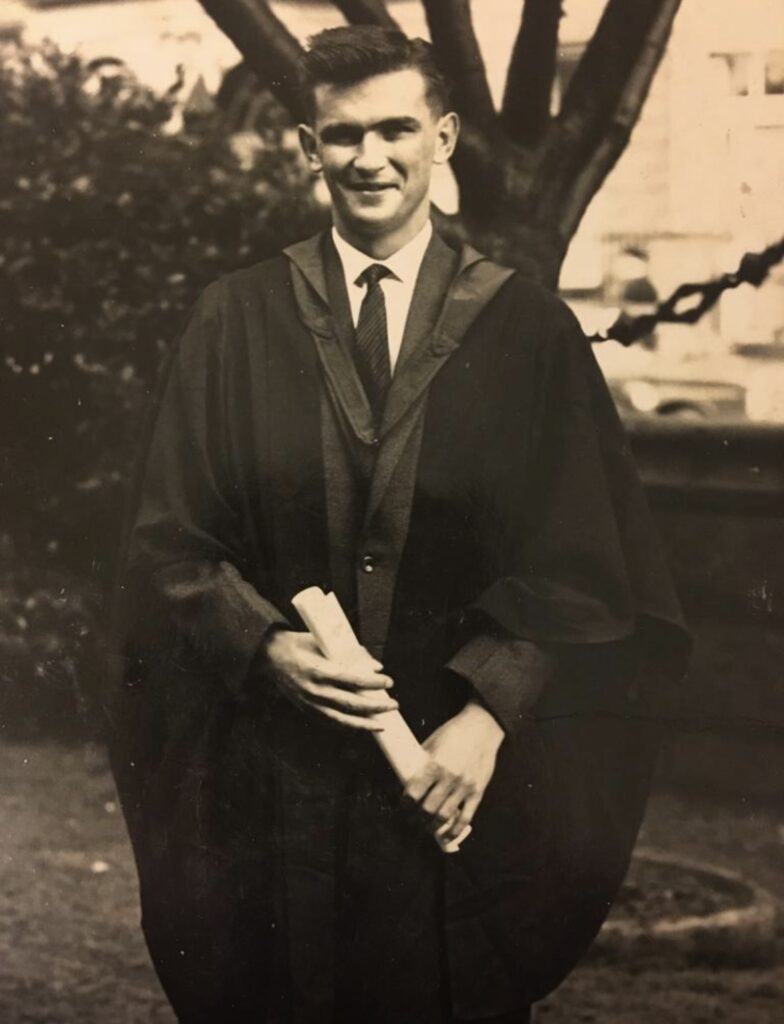

Paddy Ahern’s Obituary – Died 21st February 1998 aged 57

There were many facets to Paddy ranging from medicine to military history, from gardening to bee keeping. Above all, though he was a family man, a husband to Marielle and a father to Rory and Tania. Paddy knowing that his time was limited, started a journal of his life which, sadly was not completed. His last entry refers to his family and the quote from it is “Suffice it to say that my love and pride in all three knows no boundaries and their very existence gives me the strength and determination to carry on”

Determination was an essential part of Paddy’s character. From a young age in Ireland he resolved to become a soldier. In his journal he writes of his admiration for his Uncle Terry Barry who was killed at an early age, fighting with the London Irish Rifles at Monte Casino. Paddy always kept his photograph on his desk and considered him his role-model and inspiration throughout his life.

Paddy was one of four children and older brother of Frank, Ellen, and Terry. He was educated in Ireland, initially by his mother who was a teacher and later at a series of Schools to Matriculation level. At this point his parents had plans for him to work in a Bank. Paddy would have none of this and resolved to join the army and he didn’t really mind whether it was the Irish Army or the British Army. The Irish Army took only 20 cadets a year and he could not see himself at Sandhurst.

He discovered, however that there were always openings in the Royal Army Medical Corps – so Paddy became a Doctor. He qualified from Dublin University at the age of 22, the youngest in all Ireland that year. Paddy was in a hurry!

After resident posts in Dublin and Cork, Paddy at last joined the British Army and served for 5 years in the RAMC. His first posting was at the Barracks in Bicester. Army drivers there were few and far between so he was issued with a UK driving licence by the Army so that he could drive himself to the scattered surgeries. On the strength of this he subsequently obtained driving licences for Hong Kong, Malaya, Singapore, Borneo, Germany, and Cyprus. He was reminded much later that he hadn’t actually passed a driving test at any time anywhere.

Two forms of transport he abhorred. The first was the bicycle which he had been forced to use to get the 5 miles to school at the age of 10. The road to school was unpaved and unsealed which was bearable in the summer but utter misery in the winter months. The second was the horse which he described as trouble at both ends and intensely uncomfortable in the middle. It came as a surprise therefore when he announced that he might join the Horse Guards.

Paddy met Michael Knight soon after he left the Army and they worked together as residents at the Brompton Hospital. There he met Marielle at the Hospital Ball and they were married. By this time he decided he actually enjoyed Medicine and went into General Practice in Sutton where he worked happily for 20 years. There I know he was held in the greatest esteem and respect.

Five years ago he discovered he had developed a rare type of Leukaemia with an estimated prognosis of 5 weeks. It is a tribute to Paddy’s determination, his faith and the superb care at the Royal Marsden Hospital that Paddy was given an extra 5 years of valuable life. He came to work with Michael Knight at St Georges Hospital preparing the patients about to undergo ERCP procedures. Many of these patients are apprehensive, anxious and often frightened. It is a tribute to Paddy’s kindly approach, chattiness and reassuring Irish accent that the amount of sedation required to do the procedure was halved over night. He was our secret weapon and the patients and staff miss him terribly.

Paddy had an intensely enquiring mind and a phenomenal memory. Many of the patients who came to the unit were old enough to have seen active military service in various conflicts. The details of their exploits fascinated Paddy and the rest of the staff when Paddy came to relate the patient’s history to his colleagues. One patient in particular, he remembered who was a butcher and a ballroom dancer. It took Paddy to discover that he had been in the Special Boat Service during the war and spent the day before D-DAY in a midget submarine on the seabed off the Normandy beaches.

Everyone, they say has their storey but it took a man like Paddy to unearth the gems.

A year ago Paddy’s condition relapsed and in spite of heroic treatment his condition deteriorated.

Paddy fought his last illness like a soldier would fight a campaign. When the final battle came he chose the ground on which to fight, the way to fight and the time. He liked to keep control. Sadly he lost the battle with courage, dignity and honour on the 21st February 1998 aged 57.

His son Rory has named his own son Patrick Ahern, I would be surprised if did not become to be known as Paddy!

————————————————————————————————————————————–

From Brickfield to Battlefield – Herbert Lewis Butler, a Reluctant Soldier

James and Lucy butler of Dartford/Sittingbourne, Kent were by no means unusual. They had a large family, 9 sons and 5 daughters. Their large family were devoted to their parents, indeed their eldest son Walter stood in for his father at his place of work in the brickfields when he was injured and could no longer work. Once he had recovered from his injuries James Butler my Great Grandfather was able to return to work, mainly thanks to Walter his son. When World War 1 broke out at least 3 of his sons joined the British Army.

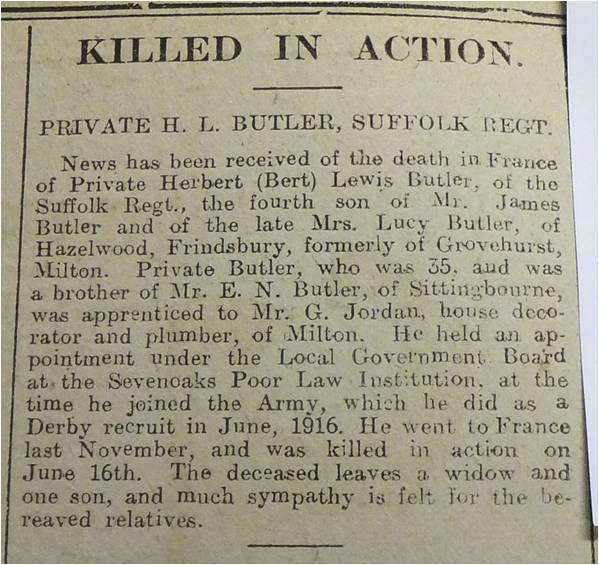

On Saturday 16th June 1917 their son, Herbert Lewis Butler was killed at the battle of Arras whilst serving as a Derby Recruit soldier. He was a private with the 2nd Suffolk regiment of infantry. His body was never recovered, and his name is now a line on the Arras Memorial wall, which today guards the road to the old front line. Most weeks there are visitors like me, distant relations paying our respects to the names of the thousands of soldiers that are immortalised here.

No doubt hoping that the war would be over before (Their mother Lucy died in March 1917 and so never knew that she had lost 2 sons) it overshadowed James life again, James had to face the fact that he had another son Edward George Butler, and just as the war seemed certain to be drawing to a close, Edward serving as a rifleman in the 2nd Battalion of the Kings Royal Rifle Corps had his life claimed by the brutality of a Gas Attack. He lies in the small peaceful CWGC Cemetery at Ligny St Flochel, severely injured in action and died soon afterwards on Saturday 7th September 1918. Reunited in death the names of the Butler brothers killed in two infamous battles, in one of the most terrible wars in history are like many others, still remembered and honoured for their sacrifice.

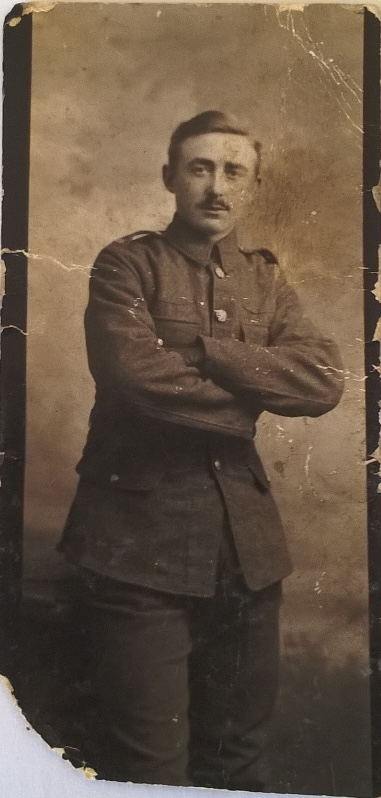

Herbert Lewis Butler was born on Sunday 6th August 1882 at Stone near Dartford in Kent. He was baptised in the Parish of St Mary the Virgin, Dartford on Sunday 10th September 1882. In 1901 he was still living with his parents at Grovehurst Milton Regis; near Sittingbourne Kent, where his father was employed in the brickfields. Herbert’s occupation at this time was an apprentice painter for one Mr G Jordan, house decorator and plumber of Milton. He married Elizabeth Ellen Watts on Sunday 20th February 1910 and they lived at 39 Heath Park Road, Romford, Essex. Elizabeth used to make Spirella Corsets (The tight Whalebone variety)

It would appear that according to the 1911 census that Herbert and his wife Elizabeth changed careers at some stage. In 1911 they both have the title “Mental Attendant” and both worked in a Workhouse in Rochford, Essex.

Herbert held an appointment under the Local Government Board at the Sevenoaks Poor Law Institution at the time he joined the Army. He joined up as a Derby Recruit in June 1916 when he was 33 years of age. This scheme was introduced in the Autumn of 1915 and was named after the 17th Earl of Derby. He was Kitcheners Director General of Recruiting and his scheme was designed to make more men volunteer for armed service and maybe avoid the need for conscription.

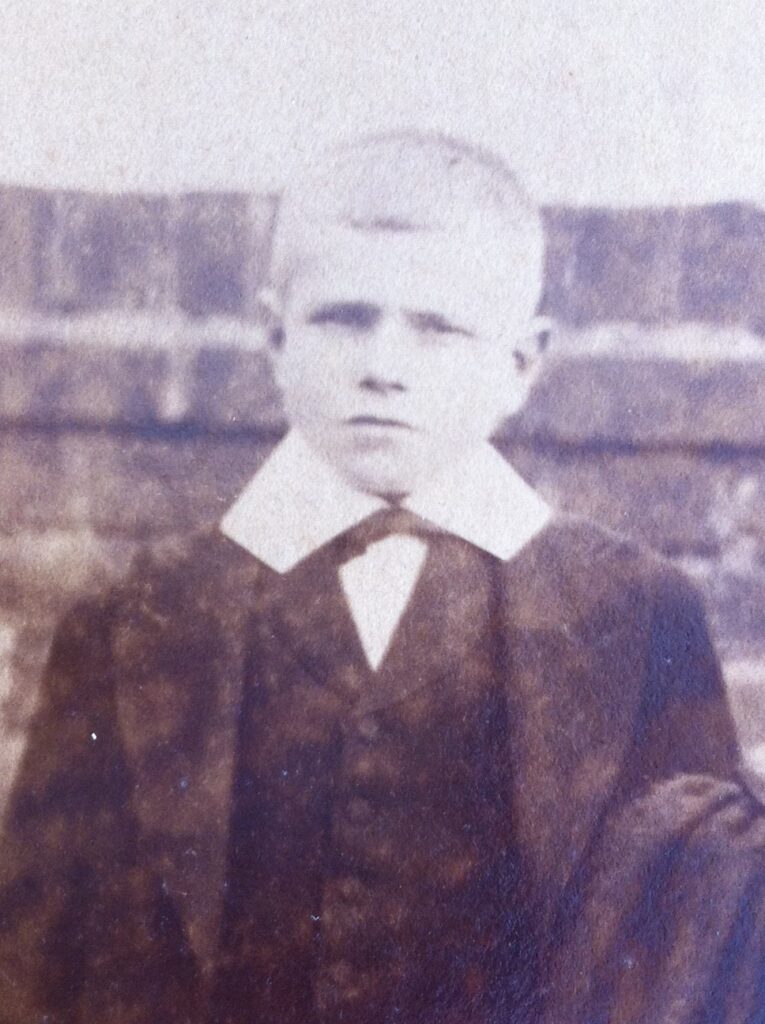

This is the best picture that I have found of Herbert Lewis Butler one of my Great Uncles, taken about 1897 when he was about 15 years of age.

Eligible men were canvassed by older men such as political canvassers or discharged veterans. These eligible men then had 48 hours to attest at their nearest recruiting office for armed service. The scheme provided over 300,000 men for the armed services, but it was not enough, and conscription was introduced in 1916.

Herbert’s initial training would have taken at least 3-4 months and then continued when his regiment, the 2nd Suffolks were posted to France in November 1916. I am sure Herbert would have had a few days leave before he went off to France, and was able to say goodbye to his wife and young son Herbert Edward who was born in 1915.

I have been unable to find out why Herbert and his wife moved to Sevenoaks or why he joined the 2nd Suffolks and not a Kent Regiment.

His battalion was to become part of the 25th Division of the British Army and was raised for Lord Kitchener’s third new army; it was to serve on the Western Front for most of the war.

The Suffolk Regiment was an infantry regiment of the line in the British Army, its history dates back to 1685. It saw service for 300 years, seeing action in many wars and conflicts, including WW1 and WW2. It was then amalgamated with the Royal Norfolk Regiment to form the 1st East Anglian Regiment, Royal Norfolk & Suffolk in 1959, and then further amalgamated with the 2nd East Anglian Regiment in 1964.

The original 2nd Battalion of the Suffolk Regiment was in France with the 8th Brigade 3rd Division in 1914. The 2nd Suffolk’s were with the British Expeditionary Force by 17th August. It was soon in action against the advancing Germans near Mons and on 25 August at Le Cateau. There the decision was taken to stand and fight. Along with other Battalions of 14 Brigade acting as the rearguard of 5 Division, they fought against overwhelming forces and despite losing their Commanding Officer and their second in command the battalion fought on for nine hours before being overrun and decimated. Losses were over 700 out of 1000. Those remaining alive were taken as Prisoners of War by the Germans, and would not return home until the end of 1918.

One of Herbert’s younger brothers, Edgar (Our Grandfather) worked for, Deans Jam factory in Sittingbourne Kent, producing Jams and Pickles. In 1915 ‘Dean’s Famous Kentish Jams’ were being sent to British Troops on the Western front. Maybe two of his older brothers who had both joined separate Infantry Regiments in 1915, occasionally opened a pot of Jam and said, ”Thanks, Edgar”.

On the 1st September 1916, the Unit diary shows that the 2nd Suffolks were being relieved by the 11th Btn Royal Warwickshire Regiment. While in reserve the battalion received much-needed reinforcements to replace their recent casualties. Throughout September the Suffolks were rotated in and out of front line trenches. When in reserve they carried out field training and battle practice. It is also recorded that one Pioneer, Sgt Murrough was sent to the base camp, for discharge after 22 years service. Lucky man.

For most of October, the 2nd Suffolk Regiment was behind the lines in reserve. While in reserve the Suffolks carried out Divisional practice attacks and training, also, the more mundane but necessary tasks, working and carrying parties in support of all troops in the front line trenches. The unit diary for October mentions several times that the 2nd Suffolks billets were on the whole very crowded and very muddy, the exceptional wet weather during October did not help matters.

During the Autumn of 1916, it is likely that Herbert had completed his initial training and was shipped to France with his fellow soldiers in the 2nd Suffolk’s, as sorely needed replacements for the depleted battalion. There would not have been much time for these newly arrived soldiers to continue their training or acclimatise themselves to France and life near the front line

It looks like Herbert Lewis Butler and his fellow replacement soldiers had their baptism of fire towards the end of the battle of the Somme. They were probably fortunate that they had missed most of the battles of the Somme, but their time was now, at the Battle of the Ancre between the 13th and the 18th of November 1916. Monday 13th November, the 2nd Division attacked Redan Ridge, but the real problem was the Quadrilateral trench, it was a huge obstacle, the barbed wire had not been destroyed by the artillery barrage, and this situation combined with the fog and the mud meant that the advance was very slow.

Elements of the Essex and King’s regiments pushed forward to their first objective with the 5th Brigade. This enabled them to position a blocking formation at the junction of Beaumont trench and Lager Alley. South Staffs and Middlesex regiments moved North East. They were confused by the presence of 3rd Division, parts of which had lost their way. The 3rd Division, which was made up of several brigades, including the76th Brigade, part of this brigade contained the 2nd Suffolks, where Herbert Lewis Butler and his fellow soldiers were on the left of the front and had lost their way. Parts of all four Battalions managed to force their way into the enemy front line trenches but were pinned down by intense machine gun fire.

Despite this mix up with their advance, the 3rd Division re-established themselves and continued their attack on Serre. However even with the support of other brigades and many machine guns, the very deep, almost to the waist mud slowed the attack down so much that eventually any small gains made, were to be lost back to the opposing German forces. Another supporting brigade also lost its direction in the confused muddy trenches and although other plans were made it was obvious that the best plan was to withdraw and reassemble the various brigades almost back to where they had begun the attack. My Great Uncle Private Herbert Lewis was somewhere in this very confusing attack and counter-attack, consisting of small arms fire, machine guns, and artillery barrages all in a morass of liquid mud. He and all the other soldiers were probably un-recognisable once the attack was called off.

Private Stanley Mack Butler of the 23rd Fusiliers, (2nd Division) a cousin to Herbert Lewis Butler was also involved in this battle, were they aware of each other’s presence? Probably not.

The 3rd Division was on the front line in the Serre area, right to the end of the battle of the

Herbert Lewis Butler was one of the lucky ones who survived this monumental battle.

Most of the precise detail of our Great Uncles “Somme Battles Experiences” was gained from “The

Somme The Day by Day Account” by Chris McCarthy, and also the 2ndSuffolk Regiment’s own War Diary/ Intelligence Summary.

1917

The first few months of 1917 were a trying time for soldiers and civilians alike as they would be challenged by another formidable adversary: the winter weather, the bitterest in living memory.

Preparations for a major offensive by the British in the area of

front.

The Germans retreated carrying out a scorched earth policy on the land they retreated over, destroying buildings, bridges and roads, making any future attacks by the allies extremely difficult. The Germans had an acute shortage of manpower as they were fighting on two fronts, with the war against Russia being a severe drain on manpower and material. This shortening of the line in the West helped relieve the pressure somewhat.

This German retreat was not noticed by the British until after dark on the 12th March 1917, which forestalled a British attack. Your average British Tommy, some of whom had been at the front for over 2 years was very likely relieved that this attack had to be postponed.

The German withdrawal to the Hindenburg Line has been explained as an Allied failure to anticipate the retirement and not being able to seriously impede it. Yet another view is that the Allies were not chasing the broken German Army but a force that was making a deliberate retreat after months of preparation. This Army now retained huge powers of maneuver and counter-attack.

The Battle of Arras took place in France in the spring of 1917 and was the main offensive undertaken by the British army on the Western front during 1917. The third Army including the 2nd Suffolks was to lead the offensive. This battle involved Tanks again and was similar to the Battle of the Somme in 1916.

It began in April 1917 and lasted for just over two months. After a positive start, the battle got bogged down into an attritional slog which ended in mid-June 1917. The final attempt by the Allies to outflank the Germans at Bullecourt proved costly for the British forces. During the Battle of Arras, there were about 150,000 British casualties and just over 120,000 German casualties.

At this stage of Herbert Butler’s war service, he was by now, a fairly experienced front line soldier. He was likely to have been very comfortable handling a rifle and bayonet and using them as efficient weapons. He had almost certainly been exposed and come under rifle fire, machine gun fire, seen grenades flying through the air and exploding, been on the receiving end of German artillery and trench mortar fire and seen horrendous wounds inflicted on his fellow 2nd Suffolk comrades in arms and other soldiers.

The following has been transcribed from the 2nd Suffolk Regiments WW1 Unit Diary from records kept in June 1917, the week Herbert Lewis Butler was killed

12 – 17 June 1917Morning brigade practice at trenches in preparation for attack. Witnessed by 3rd Army Commander Gen Sir Julian Byng V1 Corps Commander Lt Gen Haldane & divisional commander. After practice march past Acting commander on CAMBRAI ROAD. Rear being shelled with 15” for 45 mins.

For operations from June 12th to June 19th 1917 see Appendix ‘A’. During Operations the following casualties occurred : —

2 officers were killed 16.6.17 1 officer was wounded 14.6.17

2 officers were killed 17.6.17 1 officer was wounded 18.6.17

OR Other ranks in June 1917 K, killed 56, W wounded 183, m 2?

Appendix A

REPORT ON OPERATIONS JUNE 12th – 19th

by 2 ND BN SUFFOLK REGT

——————————————————

June 12th Left ARRAS 6.0 p.m. halting at the BOIS DE BOEF for issue of tools. Bombs, Ammunition and Lewis Guns, and where tea was served. Proceeded at 9.45 p.m. to the trenches and relieved the 7th K.S.L.I. Relief completed by 2.30 a.m.

The 2nd Suffolks were now in the front line trenches yet again and involved in attacking the German trenches and taking prisoners. They had to fight off German counterattacks, supported by artillery and at the same time they were digging communication trenches and improving the other trenches that they were based in. Sterling work by the 2nd Suffolk Regiment.

June 15th. 5.0 a.m. C.O. Visited the line and arranged with the C.C. right company for an organised rifle grenade shoot in combination with light Trench

Mortars on the Shell Holes in front of the division on our right. 6.30 a.m. Battalion H.Q. moved back to Pick Dug-outs. Afternoon and evening quiet

Jun 16th. 12.5 a.m. shelling of Hook Trench commenced and increased in violence up to 1.45 a.m. 20th K.R.R. and three sections of 528th Coy. R.E. worked on C.T. and Tool trench. 2.15 a.m. S.O.S. sent up, Hook trench being heavily barraged. 3.30 a.m. enemy seen in large numbers on right and left of the BOIS DU VERT; rapid fire opened and enemy stopped about 300 yards from Long and Hook Trench. 4.0 a.m enemy withdrew. 5.30 am everything again quiet. The morning was quiet but enemy registered on Hook and Tool Trenches. In the afternoon desultory shelling of Hook and Tool Trenches increased towards evening. 7.0 a.m. Shelling of Hook Trench

became heavier. 10. p.m onwards Hook and Tool Trenches heavily shelled all night and trench much damaged.

Jun 17th 5.a.m. Enemy aeroplane flew very low over our lines and observation balloon over BOIS DU VERT appeared to be observing the fire of 5.9 battery on Hook. 2.45 p.m. Hook Trench again shelled by 5.9, 4.2, and 77 mm, enemy planes flying low all the time. Midnight. Heavy bombardment opened on Hook, Tool, and Long Trenches. S.O.S sent up.

Words in italics are an exact transcription from 2nd Suffolks War Diary from the National Archives.

From reading the 2nd Suffolks World War 1 Unit Diary and in particular reading and re-reading the events on and around the date that Herbert was reported, “Killed in Action”, I think I can be fairly certain that he was on the receiving end of a German artillery bombardment and that he was killed in or around Hook, Long, Tool or C.T. Trench. Some historical records suggest that this fateful day, the 16th June 1916 was the last day of the Battle of Arras.

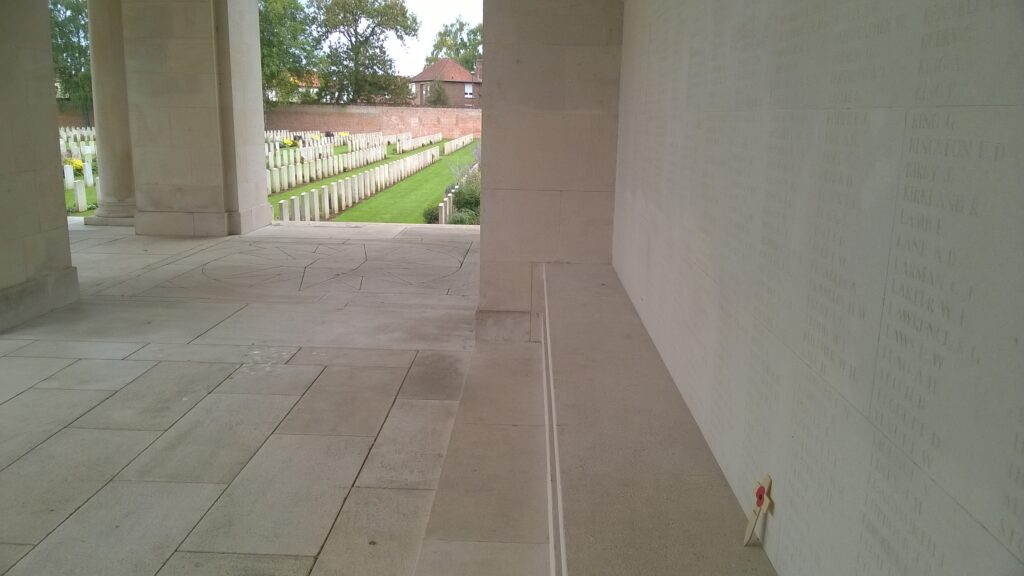

Herbert Lewis Butler was presumed killed in action on 16th June 1917, he was 34 years of age, and his body was never found. Like so many men, both young and old during the Great War, Herbert had literally disappeared into thin air. All that was left of him was his name. His name was eventually inscribed and remembered on the Arras Memorial Wall, Bay 4. The Arras Memorial commemorates about 35,000 servicemen from England, South Africa and New Zealand who died in the Arras area of France between the spring of 1916, and August 1918. They have no known grave. They will never be forgotten.

There is an unverified report that states he, “was killed in action by a sniper”. If that was the case, his body would have been recovered and he should have been buried in a marked grave. The cutting below is from a local paper and the information may have been supplied by his brother Edgar Norman Butler, my Grandfather.

Newspaper cutting from the East Kent Gazette dated Saturday July 14th 1917.

Although other battles of the First World War exacted higher casualties, the battle of Arras which began on Easter Monday, 9th April 1917 as part of a joint offensive with the French, turned out to be the most lethal of any offensive battle fought by the British Army in the Great War. The battle lasted for just over 2 months. The average casualty rate was far higher than that of both the Somme and Passchendaele. Indeed like many of the survivors later testified the Battle of Arras was the most savage infantry battle of the war.

The Arras Memorial is in the Faubourg-d’Amiens Cemetery, which is in the Boulevard du General de Gaulle in the western part of the town of Arras. The cemetery is near the Citadel, approximately 2 km due west of the railway station.

The French handed over Arras to Commonwealth forces in the spring of 1916 and the system of tunnels upon which the town is built was used and developed in preparation for the major offensive planned for April 1917.

The Commonwealth section of the Faubourg-d’Amiens Cemetery was begun in March 1916, behind the French military cemetery established earlier. It continued to be used by field ambulances and fighting units until November 1918. The cemetery was enlarged after the Armistice when graves were brought in from the battlefields and from two smaller cemeteries in the vicinity.

The cemetery contains over 2,650 Commonwealth burials of the First World War, 10 of which are unidentified. The graves in the French military cemetery were removed

after the war to other burial grounds and the land they had occupied was used for the construction of the Arras Memorial and Arras Flying Services Memorial.

The adjacent Arras Memorial commemorates almost 35,000 servicemen from the United Kingdom, South Africa and New Zealand who died in the Arras sector between the spring of 1916 and the 7th August 1918, the eve of the Advance to Victory, and have no known grave. The most conspicuous events of this period were the Arras offensive of April-May 1917 and the German attack in the spring of 1918. Canadian and Australian servicemen killed in these operations are commemorated by memorials at Vimy and Villers-Bretonneux. A separate memorial remembers those killed in the Battle of Cambrai in 1917.

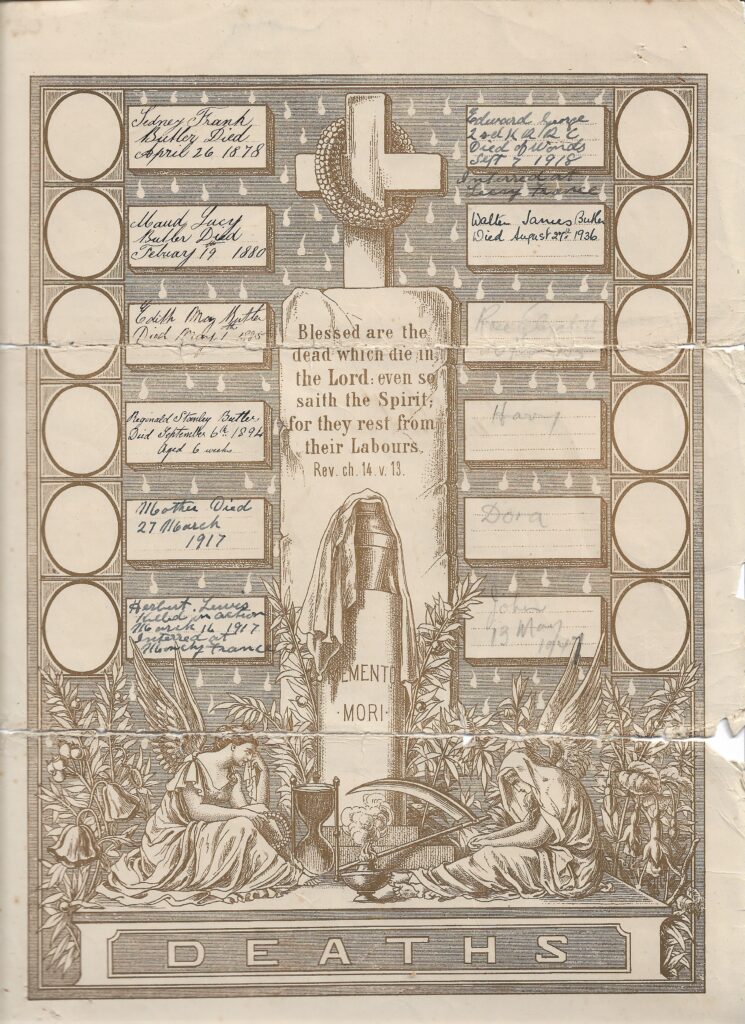

The Butler family Bible has a handwritten entry written by one of our ancestors about a hundred years ago. “Herbert Lewis killed in action” (indecipherable word) probably June,”16 1917 interred at Monchy France.”They must have had some official notice to make this insertion. Internment implies a burial, maybe his remains could not be identified when blown up. It is possible that Herbert Butler’s body was found by his fellow soldiers but there were no means of positive identification and he was initially interred at Monchy. Again it is feasible that records were lost etc, hence his name being inscribed on the Arras memorial.

His widow I am sure would have taken comfort in believing he was perhaps buried with suitable honour and care by his fellow soldiers. Monchy in France is very close to the town of Arras, which in turn is near the area of the battle of Arras.

Herbert was a soldier for just 12 months when he was killed in action

The death page from the Butler family Bible that lists the details of Herbert & his Brother George’s death during WW1.

The following paragraph was transcribed by me during my visit to France during September 2015. It was copied from the Commonwealth War Graves Commission Register 1914 – 1918 Arras Military Cemetery Register Published 2009.

BUTLER, Private, HERBERT LEWIS, 40912, 2nd Bn. Suffolk Regiment.16 June 1917.Bay 4.

According to Herbert Butlers Medal Index Card (On file at the National Archives) he was awarded the British war medal 1914-1920 and the Victory Medal 1914-1918.

His immediate next of kin should have received and been eligible for the Memorial Plaque and Scroll; however, they would have had to fill in an appropriate form to receive these items. The Plaques were made of Bronze and gained the nickname from soldiers as the “Dead Mans Penny”, mainly because it looked something like an oversized penny. Over a million plaques were issued and some were still issued in the 1930s. The accompanying letter had a copy of the Kings signature inscribed at the end of the commemoration.

The following first paragraph is a direct transcription from the Index of Wills and Administrations.

Extract from (Index of Wills and Administrations) 1918

BUTLER, Herbert Lewis of Birchfield House Sundridge Sevenoaks Kent private 2nd battalion Suffolk regiment died 16 June 1917 at Arras France on active service Administration (with Will) London 18 January to Elizabeth Ellen Butler widow. Effects £134 -17s. 1d.

Soldiers Effects Registers show the money paid by the British Government to the next of kin of men killed in action in WW1 – Herbert Lewis Butler’s widow, Elizabeth Ellen Butler received £5 – 8s & 11d. during1919.

When taking inflation into account, the payment of £5 is equivalent to just over £450 in today’s money. The government of the day was committed to providing financial support to families of those killed in action, the sheer volume of deaths meant that the sums offered by the War Office seem relatively minor by today’s standard

Apparently, Herbert’s Widow Elizabeth often used to come and visit our Grandparents Butler, Edgar our Grandfather was her brother in law.

My visit to France during September 2015 to visit research and pay my respects to our Great Uncle, Herbert Lewis Butler 1882 – 1917.

The Arras Memorial France.

Herbert Lewis Butler – Remembered – Arras Memorial Wall, Bay 4. The photo on the left with the Poppy Cross is where Herbert Lewis Butlers name is engraved on Bay 4. The photo on the right with the Poppy Cross is the same Bay but showing more names. The Arras Memorial France.

As far as I know, Herbert Lewis Butler’s Military service records were part of the infamous “Burnt” records. A large percentage of Military service records were destroyed in a fire caused by German bombing during World War 2.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————

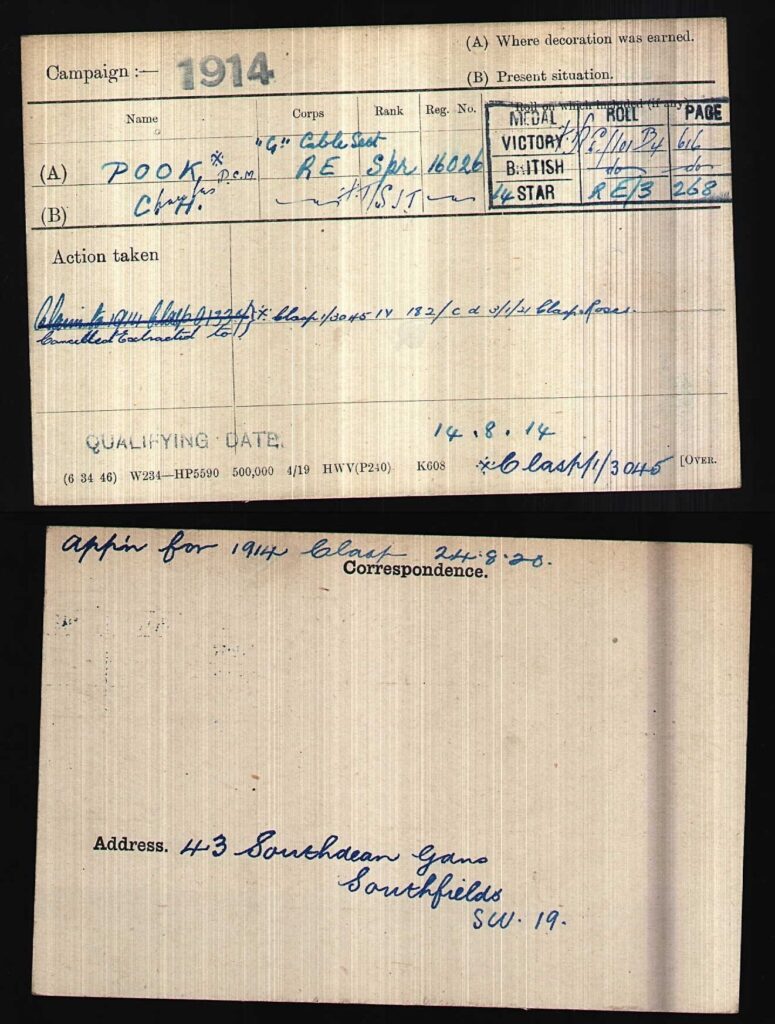

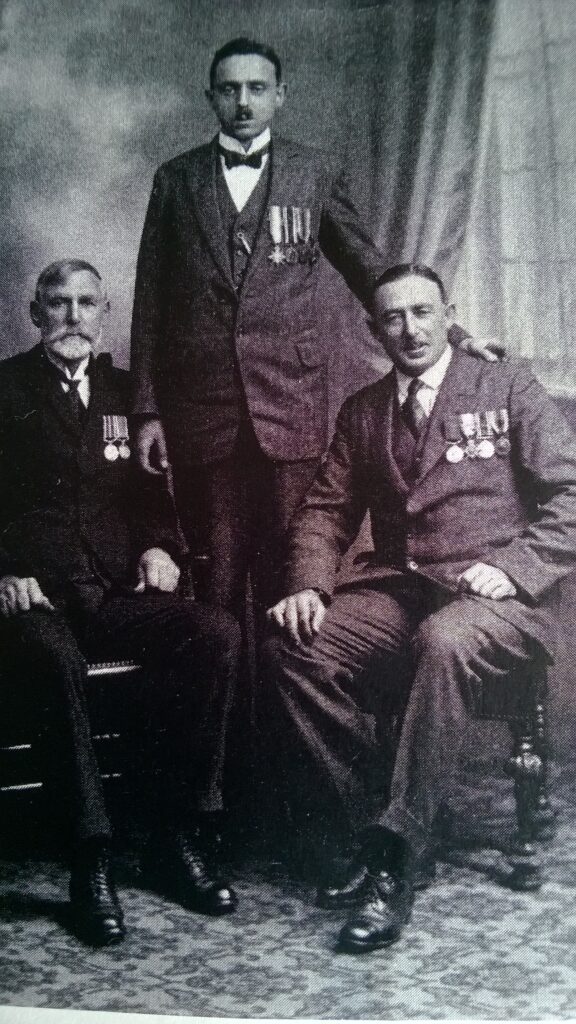

Charles Henry Pook – One of our Great Uncles

1891 – Charles Henry Pook born in St Helier, Jersey, the Channel Islands. His father John Pook, RSM, South Lancs Regiment was stationed here with his growing family for several Years.

1906/07 – Charles Pook joins the Cadet force of the Royal Engineers aged 15/16

1911 – Census Return for Monday 3rd April 1911. Charles Pook aged 20 years is stationed in Barracks in Aldershot, Farnham in Hampshire. He is part of the 1st Division Royal Engineers with the rank of Sapper and his skill set is Telegraph Lineman.

28th July 1914 – World War 1 begins. Charles Pook is by now a full time Professional Soldier in the Royal Engineers, G Cable Section, 74th Field Company. He arrived in France with his Field Company on the 14th August, 1914, and fought in the Battle of the Mons. Years later in the 1930s while he was working as a Telegraphs Inspector in East Africa he wrote the following piece for the Tanganyika European Civil Servants Association Journal, titled The Eve of Mons.

THE EVE OF MONS — (By C.H. Pook)

August the 22nd, 1914, dawned with that peculiar heavy stillness that ushers in a perfect summer’s day in Northern Europe and witnessed the two Army Corps of the British Expeditionary Force assembling for a forced march to the Franco-Belgian Frontier.

The Signal Section to which I belonged, prepared to pick up a Field Cable Line and I went ahead – to disentangle its coils from hedgerows and encumbrances that guarded its precious lengths form harm – mounted on a pony which had recently graced the shafts of a milk cart and which fell in perfectly with my stop and start progress. Otherwise, gloriously free from discipline, I was able to enjoy the new countryside into which fate had thrust me.

The first of the famous war rumors had started that morning, when a French Interpreter – resplendent in French Cavalry uniform, as compared with our drab khaki – positively stated that “so eager was the French army to meet its hereditary foe that the British army was being kept in reserve.” This news added greatly to our admiration of the French army in general and the Interpreter in particular. Along the highroad expectancy of conflict was omnipresent. Farmers and laborers seemed to be neglecting husbandry to watch the long columns of troops endlessly marching towards the Border. En route, a detachment of heavy French cavalry was passed, leading their horses with terrific saddle sores and all looking war-worn.

Dismounting at the gate of a small village school to undo a “tie,” I found myself surrounded by a number of French infantry who were bivouacking there. One of them, in English, asked my opinion of the war. The interpretation of war news between the Frenchman and myself held up the job a good deal, but seemed to cement the entente. As I mounted he remarked “The war can only last three months” to which I replied “I hope it will only last three weeks”, and rode off amidst great cheering.

The late afternoon found me craving for refreshment and an empty stomach launched me into my first estaminet. After the ritual of watering and feeding the pony (who was showing every sign of wanting to give up the war) a kindly woman set before me a meal of red wine, bread and a cheese which made itself known immediately. My offer of payment was emphatically refused, for the British Army in those days was more than welcome.

And so on through the late hot afternoon, passing columns of our infantry making their forced march with no military bands; just solid hard foot-slogging. Brigades of artillery with their guns covered in green branches and a solitary aeroplane coming into view occasionally. A railway siding was passed with an improvised ambulance train composed of the well-known “8 chevaux – 40 hommes” goods wagon.

The late evening saw the job finished and rejoining the section we moved on through the French fortress town of Maubeuge which looked very mediaeval; a glimpse through the portals of the cathedral giving a vision of coolness and peace; then out through the town gates. Here, newly turned earth-works, field guns and garrison formed a first line of defence; the whole ensemble looking the exact counterpart of a picture I had seen in an 1870 illustrated war paper. Complete with the red trousers, blue surcoat and kepi of the French sentries.

Sunset saw the end of the great trek and the section turned into an orchard for the night. Needless to say, within an hour, there was a tremendous row with the proprietor over his tasty apples which were being prematurely pulled, but the row subsided with a grimy object in a dirty vest – the cook, stirring vigorously at his dishes – began to shout “Come and have a good feed before you die”. This remark was not at all popular and it certainly took the edge of my appetite, until things were evened up by an old soldier giving authentic episodes of what had happened to facetious cooks during his previous campaigns.

That night wound up with a glorious scrap between two artillery drivers who were camped in an adjoining field and a rough ring was formed round by a mixture of all sorts of units. Goodness knows from where they got the news. At the conclusion of the fight the audience reckoned they would willingly pay to see another like it – and nobody seemed to worry about to-morrow just then.

And so to a soldier’s bed; physical tiredness, mother earth and the whispering winds of the night. I think we all sensed we were in for a particularly “rough-house” the next day, and, as you know now, we were not far wrong.

******************************

Charles sister, Florenz Pook visited “ The Battlefields of N. France (1914 – 1918 War)” in 1920/21 and wrote the following.

“We set out from Lille by train to visit Ypres where my elder brother fought during all the battles for Ypres and was present at the funeral of the Prince (Imperial) and who was given full military honours at his burial in the face of the fierce onslaught going on. We saw his tomb in the small churchyard just outside the Menin Gates.” The Prince Imperial who was a Grandson of Queen Victoria was killed in action on 27 October 1914 and buried on 31st October 1914.

1915 – Bethune

“My older brother told me of once during 1915 he and a couple of other R.E.’s had to shelter from a terrific bombardment in one of these shell holes whilst out on their telephone repairs and far from their unit – the shells were so continuous that they had to shelter for two days with only one bar of chocolate which my brother happened to have and shared with the others. Hunger drove them out and one night they crept out to try and find food. They came to a farm but at first the occupants who were in the cellar would not reply to their knocking – thinking they were Germans – but at length they realised it was English voices and they admitted them and gave them help.”

1916 – No Record as yet of where Charles Pook was during 1916, we can only presume he was still in France or Belgium during this time, or maybe had some well earned leave back in the UK?

1917

Charles was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal, which was mentioned in the London Gazette on the 1st May 1918. The Distinguished Conduct Medal was awarded to, No. 16026 Lance Corporal (A/Sergeant) C.H.Pook, 74 th D. N. Signal Company, Royal Engineers.

For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty on 6th November, 1917. Whilst laying a cable to advanced brigade report centre, his party came under shell and rifle fire. Placing his wagon under cover, he then proceeded to lay by hand. On his arrival at the report centre, hearing that the objective being attacked had been captured, he volunteered to lay cable to this point and accomplished this task. Throughout the action his courage and cheerfulness inspired all ranks in the highest degree.

Charlie Pook’s Medals and his Medal Card appear below.

1918

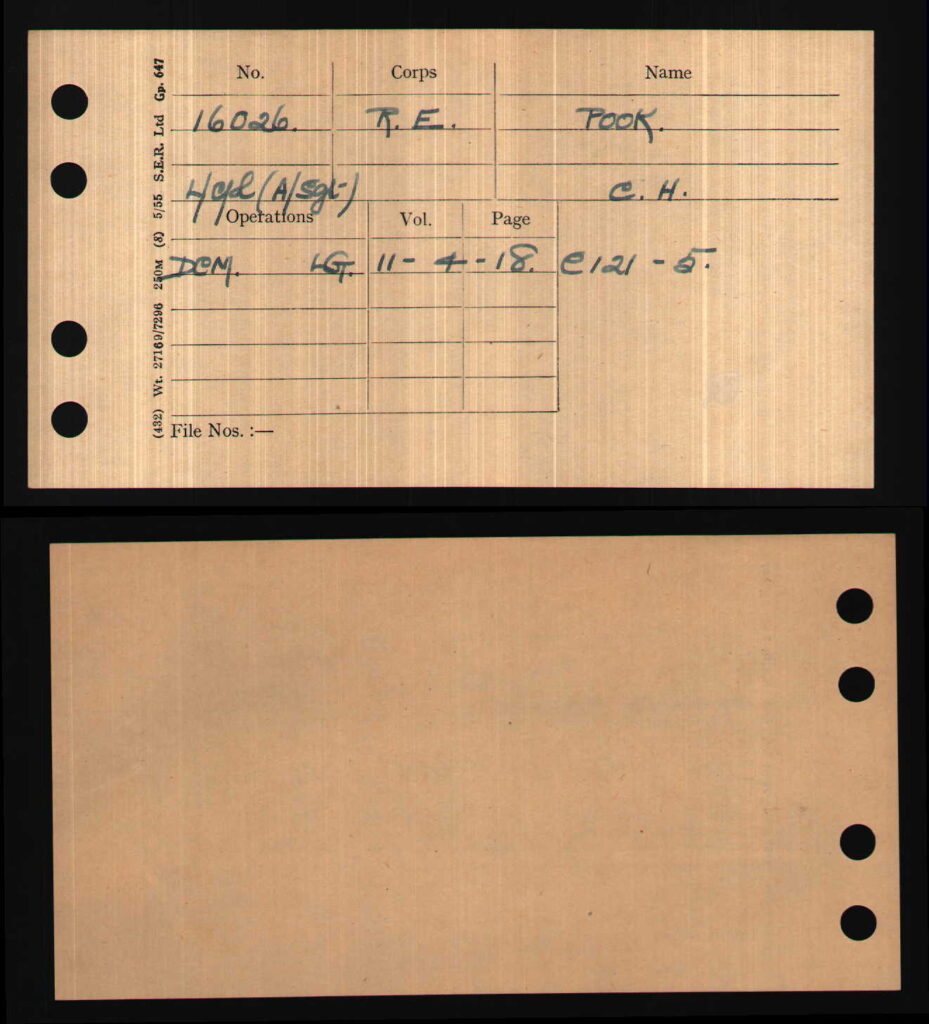

1918 and beyond? We cannot be sure where Charlie served during 1918 and beyond? The 74th Field Company, Royal Engineers in which Charlie served may have been split up as there is a record of this Field Company serving in the Middle East between 1916 & 1919. Charlie was definitely with the same 74TH Company in France during 1917.

However there is an undated Photo, probably of Charlie & other soldiers in the Middle East. There are other vague recollections from his sister Florenz that he served in the Middle East with the Royal Engineers but nothing definite.

This Photograph above recently came to light inside the Pook/Sanderson Album. All the evidence points to this photo being of Charles Pook RE, either during WW1 or just after, the uniforms, the camel in the background, the handwriting and the C inscription all point to it being Charles Pook!

As far as we can tell Charles Pook’s Military Service Record does not appear on any Genealogy or Military History/Service websites including the National Archives. It is possible that his Military Service Record was part of the “Burnt Records”, a certain amount of Records were destroyed in the Blitz during WW2.

Fortunately we inherited Charlie’s medals and copies of a few official letters, some photos and his sisters (Florenz Pook) written memoirs that included a few conversations she and Charlie had concerning some of his time spent in France & Belgium during WW1. Charlie also sent Florenz a copy of the article he wrote “The Eve of Mons”. Charles Pook’s Medal Card has also survived the test of time. With these few items we have been able to create some of Charlie’s WW1 experiences.

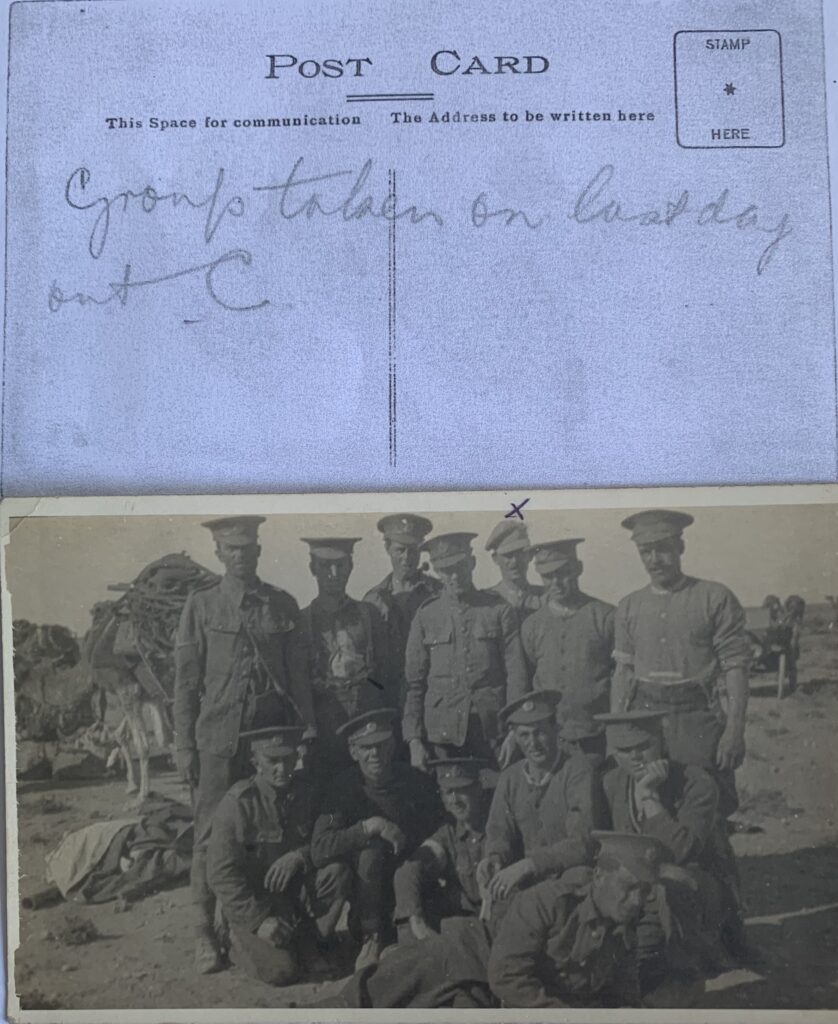

The Photo above was taken post WW1. L to R, Our Great Grandfather, John Pook, ex RSM, 1084, South, Lancashire Regiment. His sons, William John Pook, Private, 1449, ex Civil Service Rifles, 15th London Regt then Sergeant, 23433/ 23453 Machine Gun Corps, WW1 service. Charles Henry Pook, Sergeant, 16026, Royal Engineers, DCM. WW1 service.

1920 – Charles had left the Army by 1920 and had taken up a post in Africa as Inspector of Telegraphs. Charles married Mabel Daisy Spray in 1929 in London. Charles & Daisy lived in Tanganyika where Charles continued to work as the Inspector of Telegraphs. Charles died in the European Hospital, Dar es Salaam, Tanganyika, East Africa on the 22nd January, 1942, as a result of heart trouble following an operation for acute appendicitis. He did not regain consciousness. He was 50 years old. He was working hard trying to get his work up to date, ignoring his pains, and left it too late. He was buried at the New Cemetery, Dar es Salaam. Daisy remained in Africa. They had no children.

THE TRAVELS OF J.P.BARRY IN WWII

Dad’s War

I never did ask Dad the reason or reasons as to why he joined the Army. Hundreds of thousands of men and women joined up before and during the war. Some were eventually conscripted, but Dad and his brother Terry joined up voluntarily. Terry in October 1940 and Dad in December 1940. We shall probably never know the reasons for Dad joining up. It may have been patriotism, a change of direction for his life, or maybe Dad saw it as an opportunity to change his life, or the fact that his little brother had joined up and he wanted to be part of the coming war against Nazi Germany. Maybe the Admiralty were encouraging some men to join up. Dad was working in the Dockyard as a Clerk when War broke out. Perhaps Dad thought it was his responsibility to “Do his bit.” Maybe the war had very quickly affected both of them in their separate civilian lives and left them with a moral duty to join up. At this stage of WW2 it was still regarded as “The Phoney War!”

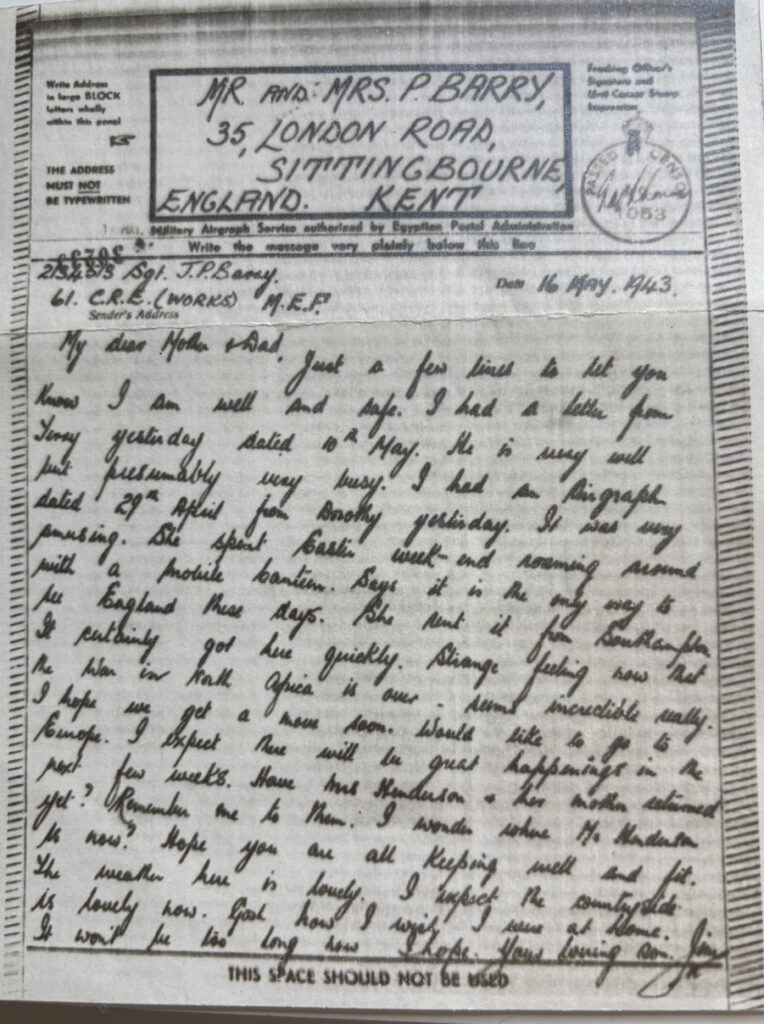

Whatever the reason was for Dad joining up, he decided to record his travels during the war either in a notebook or diary, this action was completely against Military regulations and was probably done covertly. I am sure there were many men and women like Dad that did this. When I first became aware of Dads record of his war years I originally I thought that it saved us all a lot of research and questions. Many years later it saved us asking him “What did you do in the War Dad?”

That was until I decided to look a bit further at Dad’s meticulous records and found a few things that Dad for whatever reason did not record, more of this later, all will be revealed……. Eventually. I am still compiling and recording the possible/probable missing bits of Dad’s War! Watch this Space, hopefully sometime soon!

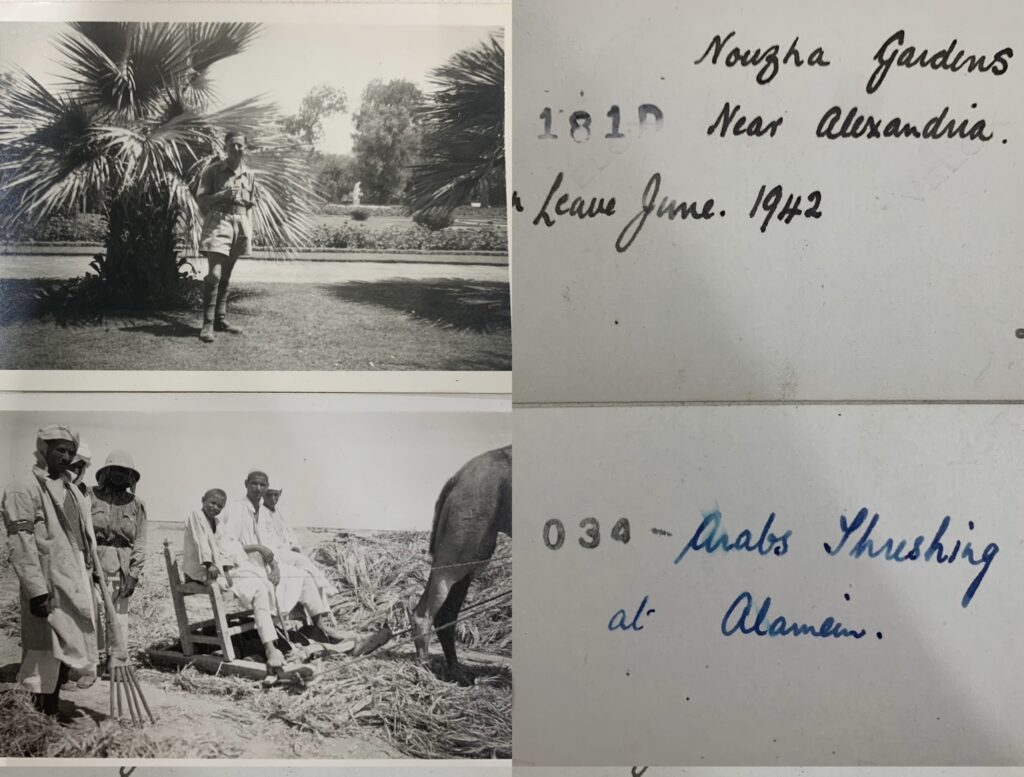

This written record and the fact that Dad also managed during the war to make a vast photographic record of his extensive Royal Engineer service and went to the trouble of dating and annotating most of these photos and post cards. Fortunately a great number of the post cards and Photos that Dad kept and or sent home were saved and preserved.

I think Dad must have kept a diary while on active service in the Uk, North Africa and Italy I do not think even he would be able to remember all these places and dates and then transcribe them. Or did he jog his memory from his photos and postcards. If he did keep a diary what became of it and was anything excluded? If this was so why did it not survive, and or did he destroy it?

Dad served as a Staff sergeant in the Royal Engineers during WW2. Most of his time was spent either preparing battlefield defences prior to and after battles in North Africa and Italy. Like most soldiers he had his share of deprivations including a high fever that hospitalised him, and an attempted mugging on his person by an Arab that he managed to successfully fight off with a resounding kick of his army issue hobnail boots to the Arab mugger’s nether regions! There were probably other incidents that he did not mention or indeed record. Before he arrived in North Africa his troopship had to stop off in Cape Town where he and many other service personnel were received into ordinary South African homes with genuine and heartfelt hospitality. Once he and his fellow soldiers had enjoyed a short period of time ashore and the troop ships had been re- fuelled, provisions replenished, they then continued to their final destination, the port of Alexandria in Egypt just over 2,000 miles from their embarkation port of Glasgow, where Dad was promptly sea sick for the first time in a 2,000 mile sea journey while his troopship was in Alexandria Harbour!

Once in North Africa Dad was able to gaze on the Pyramids, final resting place of the Pharaohs’, courtesy of the British Army. Not that Dad ever mentioned the Pyramids in his “Travels”! In the course of his duties he lived, travelled through and worked in some famous battlefields in Egypt and Libya including El-Alamein, Tobruk, and Mersa Matruh.

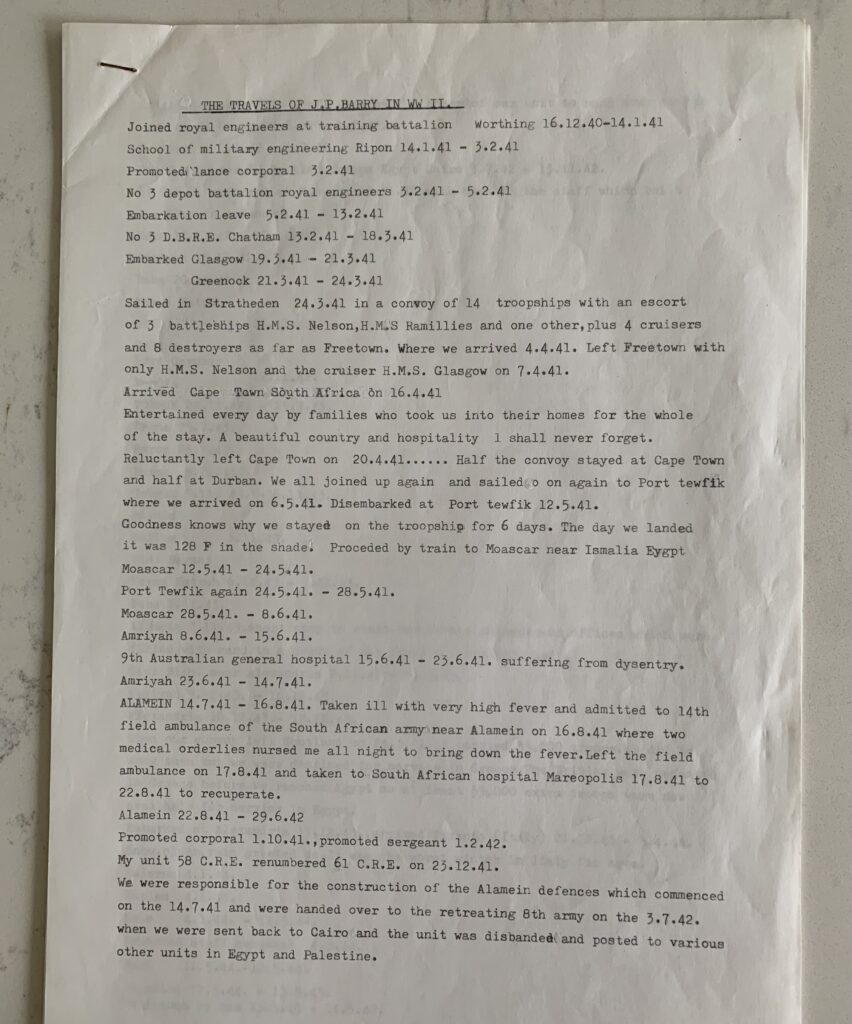

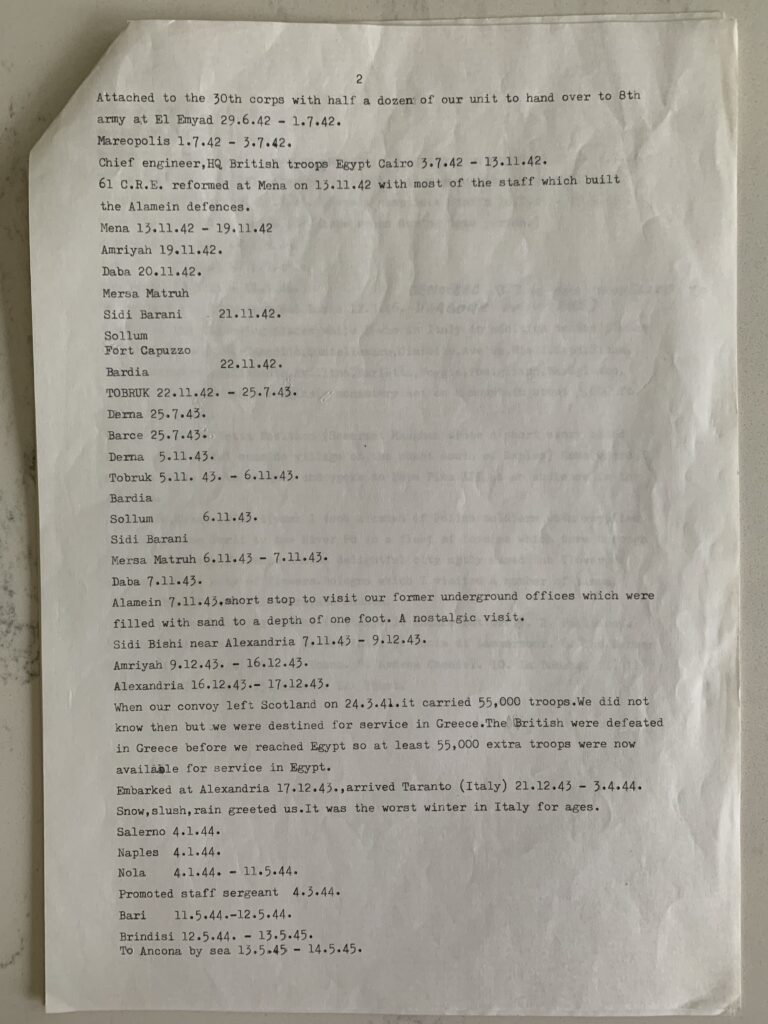

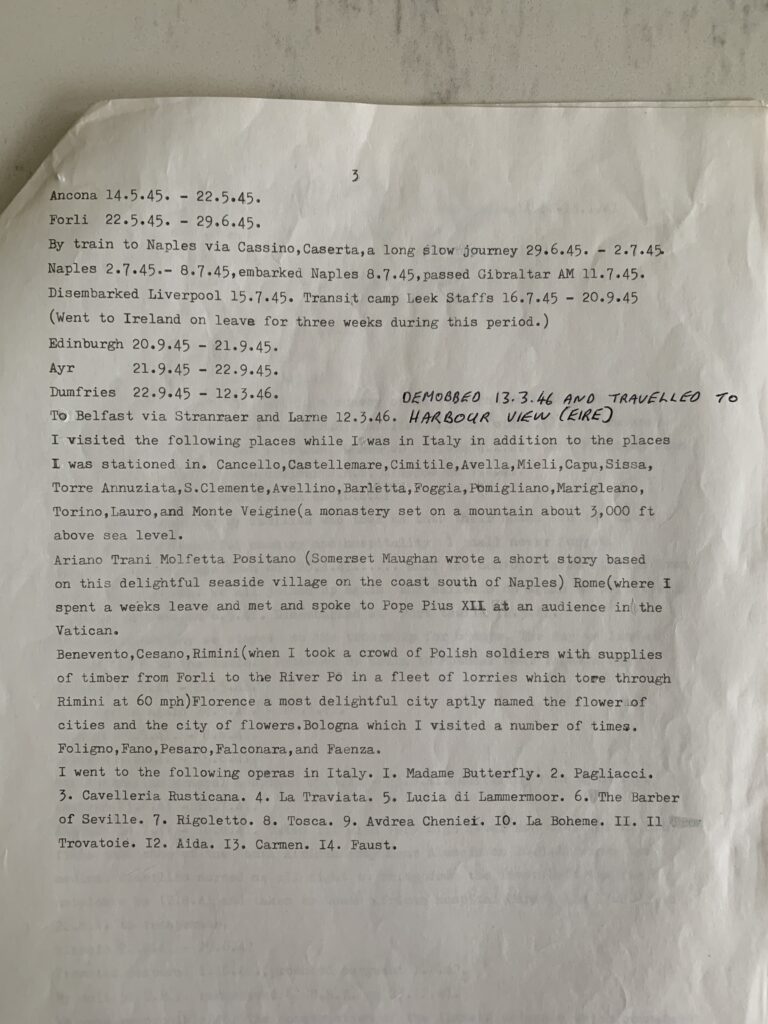

Dad’s own account of his War follows here. – THE TRAVELS OF J.P.BARRY IN WWll

The copies above are Dad’s typed “TRAVELS OF J.P.BARRY IN WWII” I also have the same “TRAVELS” but in Dad’s longhand. The typed & the long hand copy are essentially the same.

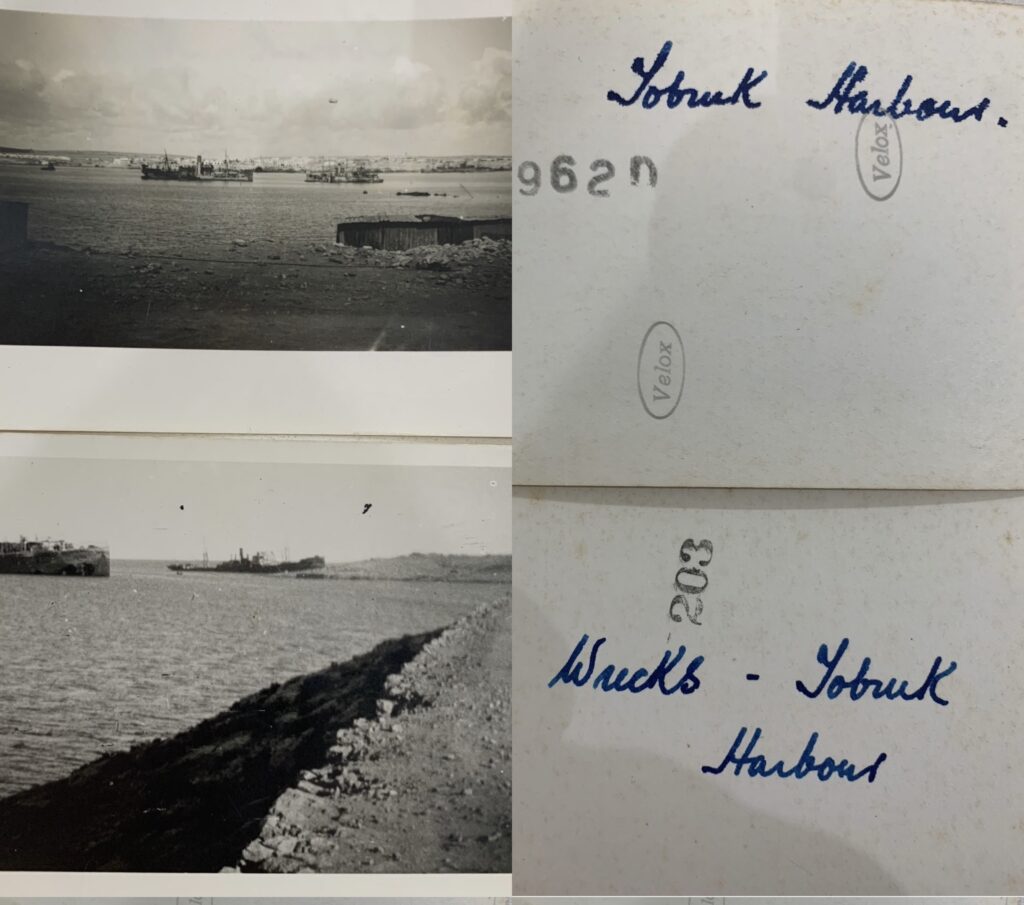

The above photographs annotated by Dad are not dated, so we have to presume according to Dads written record that he was in or close to the famous Tobruk around 1942/1943.

Dad was at Alamein before and after the famous battle of El-Alamein so these photos must date to either 1941, 1942 or 1943.

The above tatty/torn photos of Dad are I believe part of a larger contact sheet taken some time during or maybe after WWII.

Dad is pictured above wearing his Africa Star Medal Ribbon with 8th Army emblem. This ribbon was issued in 1943. Dad, like many others must have been very proud of his Desert Rat Medal. Most Medals were not awarded until the end of the War in 1945. Photo probably taken in Italy 1943/1944.

Dad did on occasion talk about some of his war experiences but you had to catch him at the right moment, if you didn’t catch him at the right moment he would change the subject and it would not help if you badgered him about it. Dad would never be Badgered! Sometimes he would talk seriously about his time in the army and then at other times he would talk about his war time service in another fashion. It nearly always started with a phrase that I believe Dad invented, and I shall never forget! He would say something like, “Of course we wouldn’t have won the war unless,” Monty and I managed to get things done!”

To put things into perspective you need to go back to Bernard Montgomery’s wartime service during WW1. Monty, remembering the distance between senior officers and men that had horrified him in the 1914/1918 war, meant that he was determined that this should not happen again: Amongst many things that Monty did that were different from many commanding officers was that he visited the units, talked to the men, arranged for cigarettes to be distributed, Dad would have been made up Free Fags!!

General Bernard Montgomery and his team did have a massive effect on the war in the desert, managing to swing the war in the allies favour and bring victory after victory to the allied armies. He managed to continue directing and winning battles when the allied armies continued the war into Europe and he carried this on right to the end of the war, helped by his team, but also his dynamic personality and the way he related to the common soldier. His experience in the battle for France in 1940, combined with his meticulous planning, his insistence on training at all levels, and many other talents helped him to win many battles.

You can understand why so many soldiers looked to him as the man to do the job and do it well. Dad was just one of his many thousands of “Desert Rat,” fans. Hence Dad’s phrase, and I do not know where it came from, or even if Dad invented it.

“Monty and I” ………

Perhaps it was because the soldiers saw Monty as a General who got things done, talked to the men, and after winning the Battle of El Alamein showed them that they could outwit Rommel, the Desert Fox.

Maybe Dad did see Monty from time to time when he pursued his duties with the Royal Engineers in North Africa, and maybe they did wave to each other as they passed each other on the North African desert tracks. We shall never know for sure. However, Monty made it his business to visit virtually every unit of the 8th Army, formally and informally. So it is quite possible that Dad did meet Monty!

As far as I am aware Dad did not photograph or talk about seeing the Pyramids despite the fact that he must have seen them while he was in Cairo for a few days & also while at the Mena house hotel!! 1 Of 7 wonders of the World & over 4,000 years old & he never mentions them! What else did Dad see in WW2 on his travels that he didn’t mention???!!!

Below is an edited version of Dad’s travels where I have inserted in Green text / italics, events that Dad may have witnessed/ experienced and not recorded on his typed “Travels”, and other relevant information.

THE TRAVELS OF J.P.BARRY IN WWII

Joined royal engineers at training battalion Worthing 16.12.40 – 14.1.41.

School of military engineering Ripon 14.1.41 – 3.2.41

Promoted Lance corporal 3.2.41

No 3 depot battalion royal engineers 3.2.41 – 5.2.41

Embarkation leave 5.2.41 – 13.2.41

No 3 D.B.R.E. Chatham 13.2.41 – 18.3.41

Embarked Glasgow 19.3.41 – 21.3.41

Greenock 21.3.41 – 24.3.41

Sailed in Stratheden 24.3.41 in a convoy of 14 troopships with an escort of 3 battleships H.M.S. Nelson, H.M.S. Ramillies, and one other plus 4 cruisers and 8 destroyers as far as Freetown. Where we arrived 4.4.41. Left Freetown with only H.M.S. Nelson and the cruiser H.M.S. Glasgow on 7.4.41.

April – November 1941 The siege of Tobruk. The Axis forces trapped the Allied forces in Tobruk for 241 days.

Arrived Cape Town South Africa on 16.4.41.

Entertained every day by families who took us into their homes for the whole of the stay. A beautiful country and hospitality I shall never forget. Reluctantly left Cape Town on 20.4.41 ……Half the convoy stayed at Cape Town and half at Durban. We all joined up again and sailed on again to Port Tewfik where we arrived on 6.5.41. Disembarked at Port Tewfik 12.5.41.

Goodness knows why we stayed on the troopships for 6 days. The day we landed it was 128F in the shade. Proceeded by train to Moascar near Ismalia Egypt.

27.4.1941 Monty moved to Tunbridge Wells to take command of 12 Corps.

Moascar 12.5.41 –24.5.41.

Port Tewfik again24.5.41 – 28.5.41.

Moascar 28.5.41 – 8.6.41.

Amriyah 8.6.41 – 15.6.41

9th Australian general hospital 15.6.41 – 23.6.41 suffering from dysentery.

Amriyah 23.6.41 – 14.7.41.

ALAMEIN 14.7.41 – 16.8.41. taken ill with very high fever and admitted to 14th field ambulance of the South African Army near Alamein on 16.8.41 where two medical orderlies nursed me all night to bring down the fever. Left the field ambulance on 17.8.41 and taken to South African hospital Mareopolis 17.8.41 to 22.8.41 to recuperate.

Alamein 22.8.41 – 29.6.42.

8th and 9th Jan.1942 Monty visited 44th & 46thDivisional area in the UK!

Promoted corporal 1.10.41., promoted sergeant 1.2.42.

My unit 58 C.R.E. renumbered 61C.R.E. on 23.12.41.

We were responsible for the construction of the Alamein defences which commenced on the 14.7.41 and were handed over to the retreating 8th army on the 3.7.42, when we were sent back to Cairo and the unit was disbanded and posted to various other units in Egypt and Palestine.

May 1942 Monty was still in the UK and was directing exercise “Tiger” this was the last exercise he directed before taking command of the 8th Army in N Africa. This exercise was almost a dress rehearsal for the battles ahead for Monty!

17-21 June 1942 the Second Battle of Tobruk took place where Axis forces captured Tobruk.

Attached to the 30th corps with half a dozen of our unit to hand over to 8th army at El Emyad 29.6.42 – 1.7.42

Mareopolis 1.7.42 – 3.7.42.

Chief engineer, HQ British troops Egypt Cairo 3.7.42 – 13.11.42.

Winston Churchill was in Cairo from 3rd Aug – 10th Aug 1942 discussing who the future commander of 8th Army should be! Dad was also in Cairo during this period, did Dad see Winston while Winston was deciding Monty’s future?

8TH Aug 1942- Monty told he was not commanding an army re the Torch landings in Morocco & Algeria but was going to N Africa to assume command of 8th Army.

10th Aug 1942 Monty left the UK & landed in Gibraltar on his way to Cairo!

12 Aug 1942 Monty arrived in Cairo from the UK via Gibraltar to take command of the 8th Army!

So Dad and Monty were in Cairo during August 1942 but did they discuss what strategy the war in the Desert was now going to take?

Just prior to the decisive battle of El Alamein and during the battle of Alam Halfa in September 1942, the allied high command ordered that every serviceman in the Cairo area (this included Dad!) to be ”armed with rifles and ordered to take their station, if need be”. This order was given out, to enable a defence against a possible German breakthrough of Rommel’s Afrika Korps. At this stage an Allied victory in N Africa was not certain!

61 C.R.E reformed at Mena on 13.11.42. with most of the staff which built the Alamein defences.

23rd October 1942 Monty begins his carefully planned and crucial battle of El Alamein. Dad of course helped out in this battle as he and his fellow RE’s built the Alamein Defences. Dad was in Cairo during the battle of El Alamein! Monty’s 8th Army had victory at the battle of El – Alamein in Oct/Nov 1942

Mena 13.11.42 – 19.11.42

Amriyah 19.11.42

Daba 20.11.42

Mersa Matruh

Sidi Barani 21.11.42.

Sollum

Fort Capuzzo

Bardia 22.11.42

TOBRUK 22.11.42 – 25.7.43

Now when Dad did finally get to Tobruk, and was there for 8 months, the fighting was over! But while Dad was stationed in Tobruk for 8 months he apparently obtained a few days leave in Cairo during May 1943! According to Terry, his little brother, and contained in a letter home to their parents, and I quote. “It was in Cairo I met Jimmy a month ago. I rather like it as a town; it’s far more French than anything else and the woman there really do dress extremely well. They sell magnificent shoes too. Shepheard’s isn’t very striking- I had breakfast there passing through to my course just to give it the once over. The Mena house out at the Pyramids is much better in every way. I had lunch there with Jimmy- we just glanced at the Ps that time as we wanted to get back to town to a flick-good old us.”

According to Terry and mentioned in a letter he & Jimmy “we just glanced at the Ps that time as we wanted to get back to town to a flick-good old us.” The Ps were of course the VERY FAMOUS PYRAMIDS!!!! 1 OF THE 7 WONDERS OF THE WORLD, SERIOUSLY DAD!!!!! Terry did have a guided tour of the Pyramids on his return trip from Israel some time later.

Derna 25.7.43

Barce 25.7.43

Monty’s 8th Army crosses from Sicily to create a bridgehead at Reggio, Calabria in Italy on the 3rd September 1943.

Derna 05.11.43.

Tobruk 05.11.43 – 06.11.43.

Bardia

Sollum 06.11.43.

Sidi Barani

Mersa Matruh 6.11.43 – 7.11.43.

Daba 07.11.43.

Alamein 07.11.43. short stop to visit our former underground offices which were filled with sand to a depth of one foot. A nostalgic visit.

Sidi Bishi near Alexandria 7.11.43 – 9.12.43.

Dads little brother Terry was killed in action on 5th December 1943 at Monte Camino, Italy. Dad would have been informed some days/weeks later.

Amriyah 09.12.43 – 16.12.43.

Alexandria 16.12.43. – 17.12.43.

When our convoy left Scotland on 24.3.41 it carried 55,000 troops. We did not know then but we were destined for service in Greece. The British were defeated in Greece before we reached Egypt so at least 55,000 extra troops were now available for service in Egypt.

Embarked at Alexandria 17.12.43., arrived at Taranto (Italy) 21.12.43 – 3.4.44. Snow, slush, rain greeted us. It was the worst winter in Italy for ages.

Monty was recalled to Britain in January 1944

Salerno 4.1.44.

Naples 4.1.44.

Nola 4.1.44 – 11.5.44.

Promoted staff sergeant 4.3.44.

17th March (A very special day, St Patrick’s Day) 1944 Mount Vesuvius in Italy begins to erupt, Dad was 6 miles away!

17th March 1944 Mount Vesuvius in Italy begins to erupt followed by a major eruption on the 24th March which caused damage to a nearby U.S. Air base, this eruption caused a massive ash plume. The eruption and ash plume could be seen from Naples 12 miles away

.